![Accrochage [Vaud 2014] & Lukas Beyeler, Prix du Jury 2013 <br>Julian Charrière. Future Fossil Spaces, Prix culturel Manor Vaud 2014](https://www.mcba.ch/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Affiche_Accrochage_PrixManor_FR-light-1-1-2304x3216.jpg)

Accrochage [Vaud 2014] & Lukas Beyeler, Prix du Jury 2013

Julian Charrière. Future Fossil Spaces, Prix culturel Manor Vaud 2014

Das Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts Lausanne präsentiert dieses Jahr die zwölfte Jahresausstellung der zeitgenössischen Waadtländer Kunstszene, eine Ausstellung neuer Arbeiten von Kunstschaffenden verschiedener Generationen, die von einer Fachjury aus freien Bewerbungen ausgewählt werden. Ob es sich nun um Malerei, Plastik, Fotografie oder Video handelt, die kantonale Kunst der Zukunft erhält einen Ehrenplatz im Museum, um das Jahr in Schönheit ausklingen zu lassen. Für die diesjährige Ausgabe nahmen 210 Waadtländer oder im Kanton tätige Kunstschaffende die Einladung des Museums an und reichten 503 Gemälde, Plastiken, Zeichnungen, Fotografien, Videos und Installationen ein.

Für die diesjährige Ausgabe nahmen 210 Waadtländer oder im Kanton tätige Kunstschaffende die Einladung des Museums an und reichten 503 Gemälde, Plastiken, Zeichnungen, Fotografien, Videos und Installationen ein.Die für die Auswahl zuständige Jury besteht 2014 aus Aloïs Godinat, Künstler, Lausanne, Samuel Gross, Direktor Fondation Speerstra, Apples, Felicity Lunn, Direktorin Centre PasquArt, Biel, und Sabine Rusterholz, Direktorin Kunsthaus Glarus.

Der Jury-Preis 2014 wurde an Anne Hildbrand vergeben.

Die Ausgewählten Künstler.innen

Céline Amendola, Emmanuelle Antille, Sophie Ballmer, Delphine Burtin, Maëlle Cornut, Sylvain Croci-Torti, Nicolas Delaroche, Guillaume Dénervaud, Simon Deppierraz, Noémie Doge, Jacques Duboux, Livia Salome Gnos, Anne Hildbrand, Jean-Christophe Huguenin, Florian Javet and Michael Rampa, Lucie Kohler, Stéphane Kropf, Mingjun Luo, Emanuele Marcuccio, Line Marquis, Genêt Mayor, Sébastien Mennet, David Monnet, Banu Narciso, Virginie Otth, Jérôme Pfister, Stéphanie Pfister, Nicolas Raufaste, Maya Rochat, Marie-Luce Ruffieux, Léonore Thélin, Arnaud Wohlhauser.

Die Ausstellung wird unterstützt von

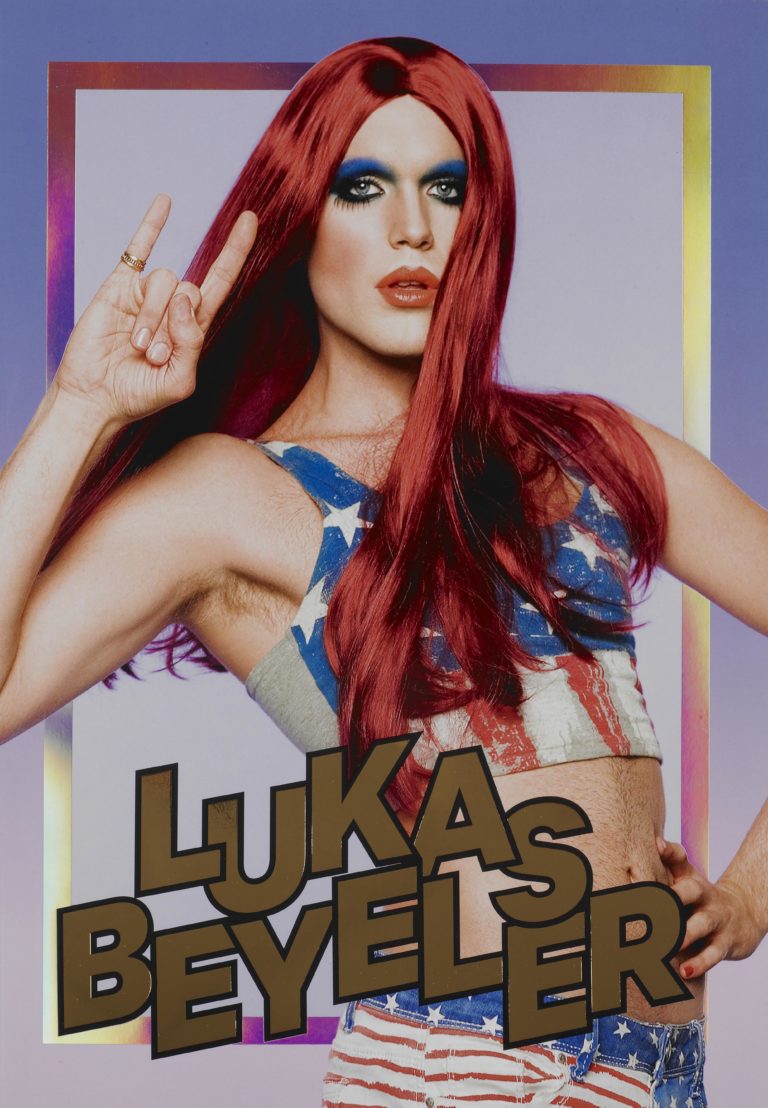

Lukas Beyeler. Instant Win. Jury-Preis 2013

Der Träger des Jurypreises 2013, Lukas Beyeler, wurde letztes Jahr für sein Video Everyone Wants Me, It’s My Biggest Downfall ausgezeichnet. 1980 in Lausanne geboren, beendete er seine Studien an der ECAL mit dem Prix Manganel. Seit mehreren Jahren lebt und arbeitet er in Zürich. Seine Fotografien und Videos zeigen Akteure und Freunde seines Zürcher Kreises in Posen und Szenarien, die sich, wie Florence Grivel in ihrem Katalogbeitrag schreibt, «in eine Tradition» einordnen, «die Pop Bilder, Gay-Glamour und Ästhetik der Eighties mischt».

Für seine Lausanner Ausstellung schuf Lukas Beyeler ein Environment, das aus einem Mix von architektonischen Referenzen und Volkskultur besteht. So wird ein Video, inspiriert von der für ihre Reliefornamente berühmten Fassade des von Frank Lloyd Wright erbauten Ennis House in Beverly Hills an die Wand projiziert, während vom Künstler nach demselben Modell geschaffene Fliesen ein künstliches

Grab in der Mitte des Raums verzieren. Der in den Raum führende Gang, der die Besucher empfängt, ist von japanischen Flipperkästen gesäumt; Japan hat den Künstler entscheidend geprägt; seit seiner Kindheit ist er von der Sprache, die er fliessend spricht, und den auf dem Archipel produzierten Gadgets fasziniert. Anlässlich der Vernissage und im Rahmen des Festival des créations émergentes Les Urbaines im Dezember 2014 orchestriert Lukas Beyeler Performances, die im Zusammenhang mit seiner Installation stehen.

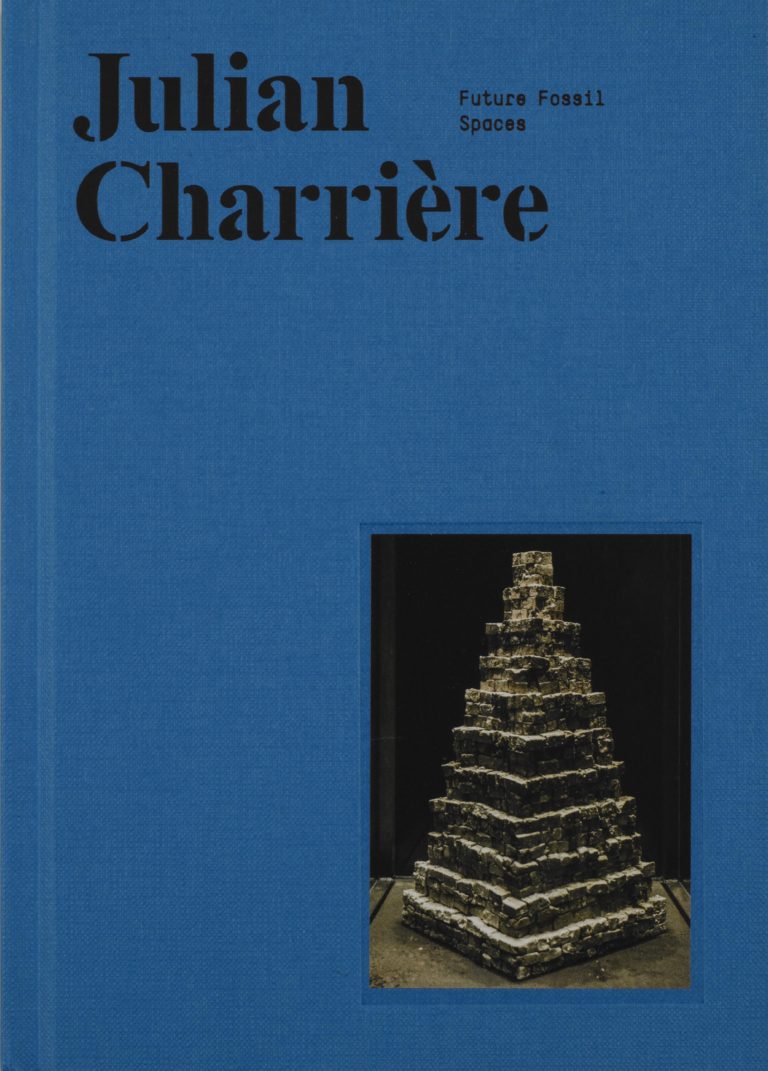

Julian Charrière. Future Fossil Spaces

Manor-Kunstpreis Waadt 2014

The Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts in Lausanne presents the first museum exhibition dedicated to Julian Charrière, winner of the 2014 Manor Vaud cultural prize. Born in Morges in 1987, he studied at ECAV (École cantonale d’art du Valais) and at the Institut für Raumexperimente in Berlin, under the guidance of Olafur Eliasson. Julian Charrière now lives and works in Berlin. His work, which is a blend of conceptual explorations and poetic archaeology, is similar to a research process which includes performances and photographic documentations as well as installations. Charrière’s works – bricks made of materials from the world’s great rivers, core samples which reveal the sediment of a Berlin pavement, globes which have been sanded until the names of territories disappear – are anchored in the physical substance of the places they explore and also generate new geographies.

The exhibition designed by Julian Charrière for the Museum brings together works for which the artist travelled to Iceland, Kazakhstan, the Atacama Desert (Chile), Bolivia and Argentina. It is entitled Future Fossil Spaces, a title which is a nod to The Blue Fossil Entropic Stories, three photographs which were taken during an expedition undertaken in 2013, when the artist climbed an iceberg in the Arctic Ocean and attempted to melt the ice underfoot using a gas blowtorch for over eight hours. The fossils mentioned in this instance do not refer to animal or mineral traces captured in rocks but to the Latin etymology, which literally means “obtained by digging”, where the artist’s action involves presenting, there and then in the exhibition space, works which are in dialectic conflict between the two arrows of time, one pointing towards the past and the other pointing towards the future. One of the works, the most understated in the exhibition, is entitled The Key to the Present Lies in the Future (2014). Twenty-four hourglasses containing sand from twenty-four geological periods are hurled by the artist against a wall of the Museum. All that is left of all those eras suddenly brought together in the same place and at the same time as a result of a powerful act are glass debris and sandy remnants. The hourglass itself is already a perfect metonymy of the link between time and space since it allows an interval of time to be measured by the movement of matter. The work echoes that of Robert Smithson, and in particular his thoughts on the issue of non-sites, and recalls one of his works in particular, Hypothetical Continent (Map of Broken Glass: Atlantis), created in 1969, a pile of glass fragments which make up the fictitious map of a lost continent.

Rather than a hypothetical continent, Julian Charrière lays out a fictitious topography, a sort of “energetic garden”, in his exhibition in Lausanne. On the ground, there are strangely beautiful coloured landscapes made from enamelled steel containers full of saline solutions from lithium deposits in Chile, which resemble an aerial view of the deposits; rising high, columns of salt bricks from the same area highlight the tension between a material of the future – lithium – and the time which has had to elapse in order to create it; further on time seems to be frozen in a display cabinet where the artist has deposited plants captured in a sheath of ice; finally, a video filmed in Kazakhstan, at the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site, closes – or opens – the exhibition on the issue of the interdependence between humans and their environment. Entitled Somewhere, the video explores the site of the first Soviet military nuclear tests, where the radiation which was released between 1949 and 1989 remains extremely high today. The desolate and timeless aspect of these landscapes, filmed in a slow motion tracking shot by the artist without any accompanying commentary, lends an unsettling strangeness to them. The past catches up with the future in a constantly expanding present.