Bibliography

Martin Schwander (ed.), Edgar Degas. The Late Work, Riehen/Basel, Fondation Beyeler, Ostfildern, Hatje Cantz, 2012: 157.

George T. M. Shackelford and Xavier Rey (eds.), Degas et le nu, exh. cat. Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Paris, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, Hazan, 2012: 248, n. 259.

Richard Thomson, The Private Degas, exh. cat. Manchester, Whitworth Art Gallery, Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, London, Arts Council of Great Britain and The Herbert Press Limited, 1987: 119, n. 158.

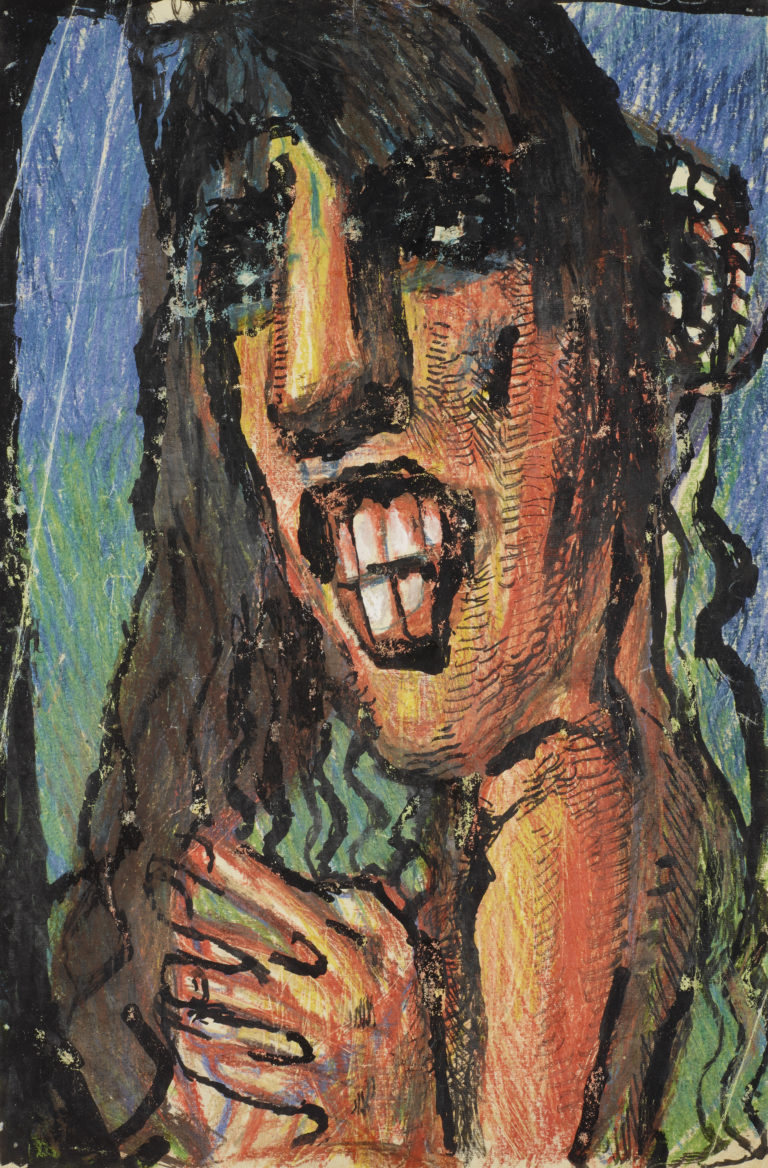

Degas produced some two hundred pastels on the theme of women washing, placing the emphasis on the action itself: the figure is presented in close up with little room for her surroundings. Here, we see a naked woman rubbing her neck. Standing and leaning forward, with her head down, she is pulling her long hair to one side in order to allow the short, energetic rubbing movements of her right hand.

As Degas constructed his drawing, he continually added and superposed the colours, merging the application of a new pastel with the previous one. To soften the texture and make it more velvety or more effectively mix the shades, he rubbed the pastel with his fingertips or with paper. He also made strong, abrupt movements that left behind thick lumps of pastel on the paper. But whereas other works by Degas on this subject play on cold hues and develop complementary combinations of oranges and greens, or reds and purples, the colours in Femme s’essuyant la nuque are warm, apart from the icy blue of the towel. The space is filled with an orange-red that extends and diffuses the pinks of the flesh and the ginger of the hair.

At the same time, Degas used charcoal not only to define the composition but also to dialogue with the pastel. Vigorously applied, in repeated, overlaid strokes that clarify the forms and bestow on them a certain monumentality, the black charcoal melds with the zones of luminous pastel colour. In a complex network of hatchings and vertical and horizontal striations, the two mediums together construct the figure’s carnal density.

Degas’ late pastels were still in his studio when he died. Their discovery in 1918 revealed an unexpected degree of artistic freedom in his work.