Bibliography

Fleur Roos Rosa de Carvalho, ‘La quintessence du noir et blanc. Les xylographies,’ in Guy Cogeval, Isabelle Cahn, Marina Ducrey and Katia Poletti (eds.), Félix Vallotton. Le feu sous la glace, exh. cat. Paris, Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, RMN – Grand Palais, 2013: 251-257.

Richard S. Field, ‘Extérieurs et intérieurs: l’œuvre gravé de Félix Vallotton,’ in Sasha M. Newman (ed.), Félix Vallotton, exh. cat. Lausanne, Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne, Paris, Flammarion, 1992: 43-92.

Maxime Vallotton and Charles Goerg, Félix Vallotton. Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre gravé et lithographié/Catalogue raisonné of the printed graphic work, Geneva, Les Éditions de Bonvent, 1972: n. 169 a.

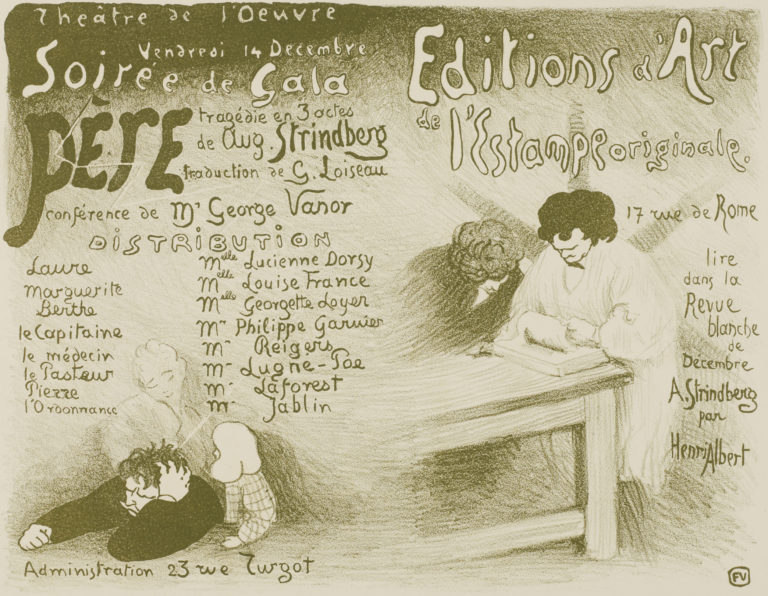

By 1900, Vallotton was renowned in Paris as one of the major protagonists in the revival of printmaking. He had begun making drypoint works and etchings in 1887, but his reputation was really established a few years later, when he became the main illustrator for La Revue blanche. He triumphed in particular with his woodcuts, a practice that he began in 1891 and continued with some regularity until 1899, when he devoted himself to painting.

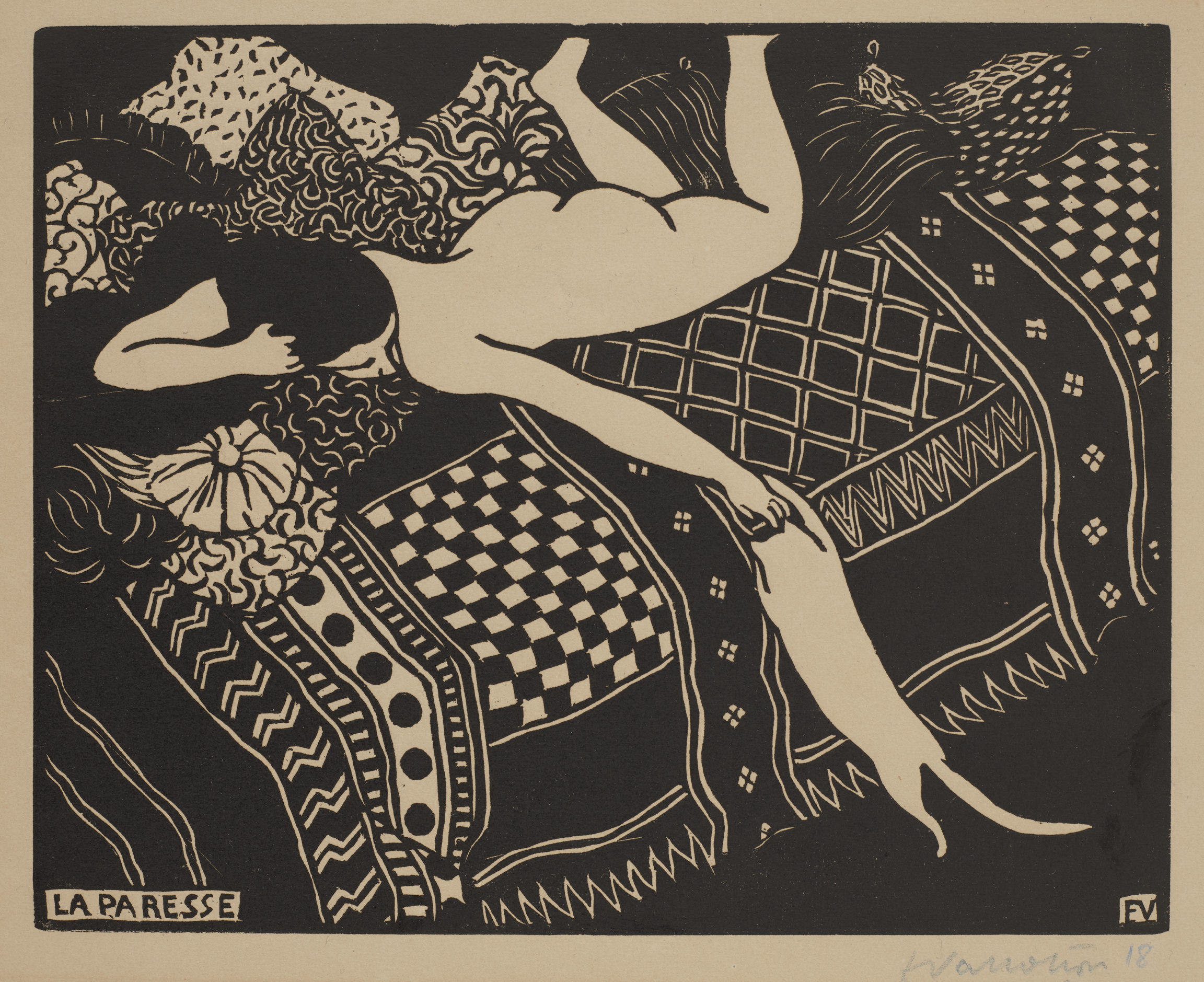

There are several factors behind Vallotton’s success. First, his choice of the woodcut, a medium that had been abandoned by artists after its hour of glory in the Renaissance. A great admirer of Albrecht Dürer, he thoroughly explored the potential of the medium: working with a vertical grain wood, he used a knife to gouge out broad, clearly defined surfaces, thus dispensing with effects of gradation. He also made the radical choice of black-and-white: at a time when his Nabi friends were producing multi-coloured posters and colourful prints, Vallotton opted for the contrast between deep black and the white of the paper. This approach served a synthetic graphic language influenced by Japanese prints. Depth was flattened, with everything brought to the picture plane, and expressivity was entrusted to line, to Vallotton’s supple arabesques delimiting zones of black, a precise line animating them with decorative motifs.

La paresse shows Vallotton’s art at its most accomplished. From the darkness he summons the naked body of a woman lying on her belly: a model, or a prostitute awaiting a client? Her feet in the air, she is lolling on a sofa covered with geometrically patterned fabric and teasing a cat that is rearing up on its hind legs. United by the whiteness of their bodies, the two partners in play embody the nonchalant freedom of those who, like artists, refuse to be tamed and to conform to the demands of bourgeois morality.