On display

The CollectionBibliography

Camille Viéville, ‘Visions d’égotisme. L’autoportrait chez Balthus,’ in Jean Clair and Dominique Radrizzani (eds.), Balthus – 100e anniversaire, exh. cat. Martigny, Fondation Pierre Gianadda, 2008: 31-36, cat. 37.

Jörg Zutter (ed.), Balthus, exh. cat. Lausanne, Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts, Geneva, Skira, 1993.

Jean Clair, ‘Le sommeil de cent ans,’ in Jean Clair (ed.), Balthus Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre complet, Paris, Gallimard, 1999: 7-56.

![Arnulf Rainer, Ohne Titel (Face Farces) [Untitled (Face Farces)], 1969](https://www.mcba.ch/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/1984-050_RAINER_num4000_em-768x913.jpg)

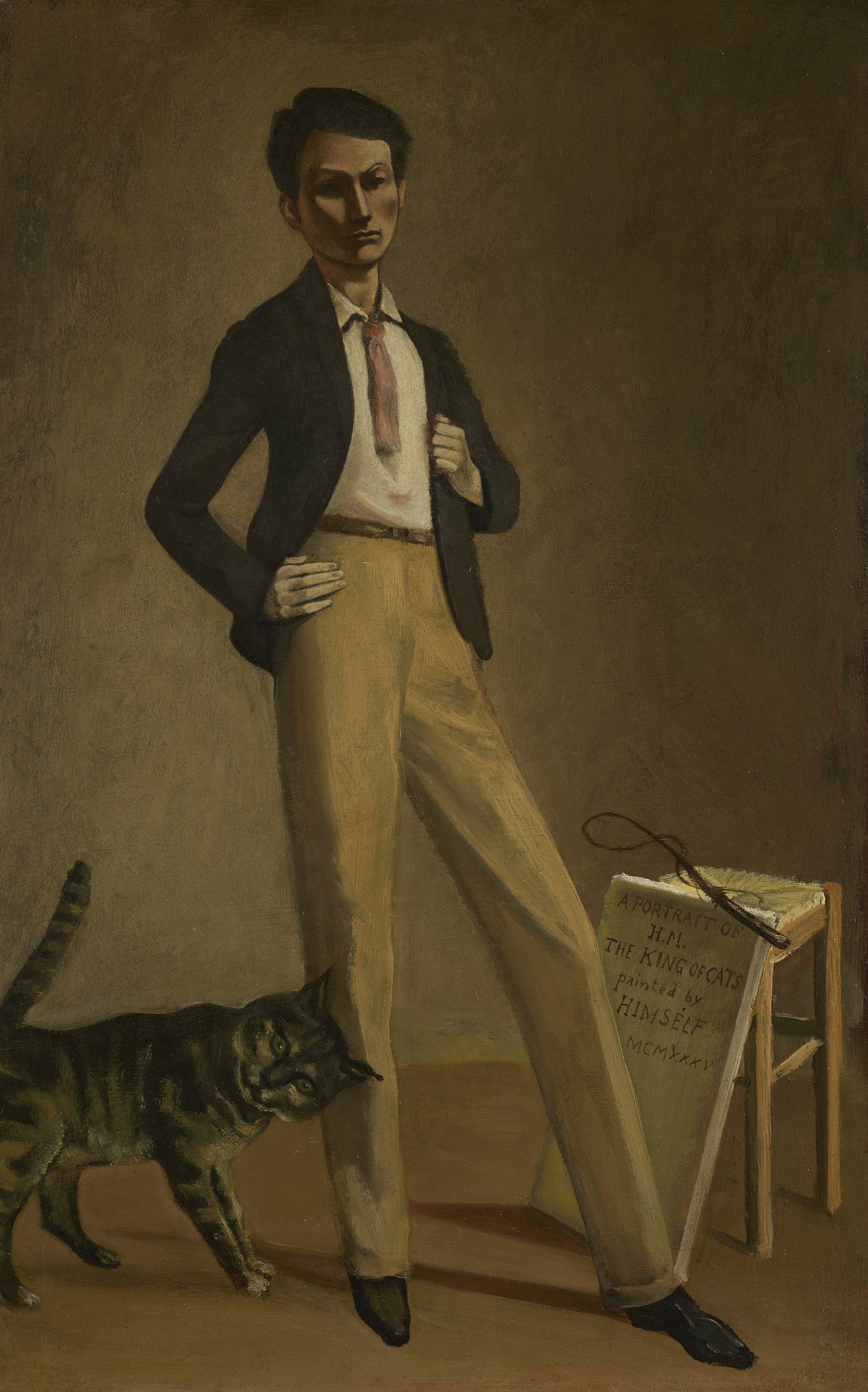

Balthus’s self-portraits depict him with a series of assumed identities in which he never drops his mask. This 1935 portrait shows him standing in an elegant outfit, one hand holding his jacket lapel, the other on his hip. A large tabby cat is rubbing up against his leg. The narrow space and harsh light that seems to fall from a skylight evoke a dungeon. The only objects in the bare-walled room are a stool, a whip and a canvas bearing an inscription in capital letters, which sheds some light on the mysterious work: ‘A Portrait of H. M. The King of Cats, painted by Himself’. The self-portrait is that of an artist and monarch who rules over a kingdom of cats.

Balthus’s Mitsou (1921), begun when he was very young, tells in pictures, the story of a cat found and then immediately lost. His obsession with cats would last throughout his lifetime. Cats – part wild animal, part household pet – have represented both freedom and the inner life of artists since the Romantic period. In 1935, the year he painted this portrait, Balthus began signing off his letters to his future wife Antoinette de Watteville as ‘King of Cats’, having seen off a fellow suitor. The victorious fiancé now reigned over the creatures that resembled him most: as he wrote in his memoirs, ‘Very early on, I grasped my secret, mysterious belonging to the world of cats. I shared their urge for independence’. In this painting, one of his subjects is showing due deference, though the whip close at hand transforms the genre painting into an allegory of the savage self that must constantly be tamed.