Bibliography

Catherine Lepdor, «Steinlen, le messager de l’art social», in Philippe Kaenel in collaboration with Catherine Lepdor, Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen. L’œil de la rue, exb. cat. Lausanne, Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts, Milan, 5 Continents Editions, 2008: 8-15.

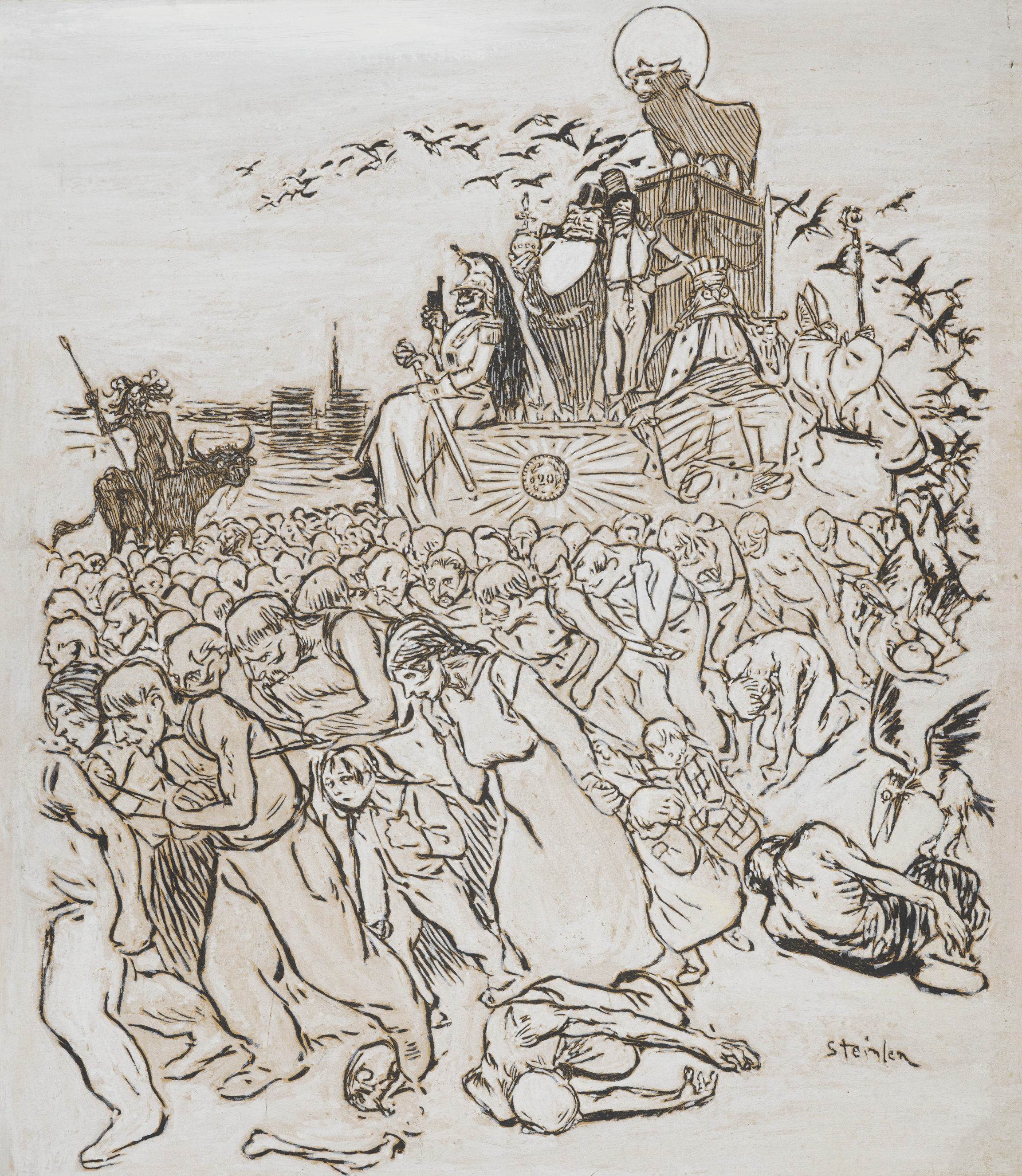

February 18, 1896, was the closing day of carnival, and the streets of Paris still rang with the noise of the riotous parade. To mark the occasion, L’Écho de Paris published on page three Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen’s design for a float for the Boeuf-Gras (fatted calf) parade. It is crowned by an effigy of the Golden Calf, the Biblical symbol of idolatry, backlit by a pale, fat moon. At the feet of the calf “phynance” (finance) is shown consorting with the archetypal swindler Robert Macaire, surrounded by the army (a skeleton in a Republican Guard uniform), Justice, and the Church. In the centre, a gold louis coin shines like the sun. The populace in the lower part of the caricature are harnessed to the float, labouring under the yoke, assailed not by handfuls of confetti but a flock of scavenging birds.

The drawing pays homage to caricaturists of the July Monarchy such as Honoré Daumier and Grandville. It owes its subversive power to the codes of the carnival, a display of folk culture dating back to the medieval period. Traditionally, carnival acted as a dampener for threats to the social order by temporarily reversing the hierarchy of power between the upper and lower classes. Here, however, Steinlen’s aim was to stoke rather than minimise social discontent. 1890s France was rocked by the Panama scandals, the brutal repression of a strike in Fourmies, and new laws limiting the freedom of expression. For Steinlen, the time for blowing off steam had passed: it was time to challenge the status quo. Having developed affinities with the libertarian movement in the late 1880s, he designed his carnival float to call for a popular uprising.