On display

The CollectionBibliography

Claire Stoullig (ed.), Francis Gruber l’œil à vif, exh. cat. Nancy, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Clermont-Ferrand, Musée d’art Roger-Quilliot, Lyon, Fage, 2009.

Antonin Artaud, Bernard Ceysson et alii, L’écriture Griffée, exh. cat. Saint-Étienne, Musée d’Art Moderne, Paris, RMN, 1993.

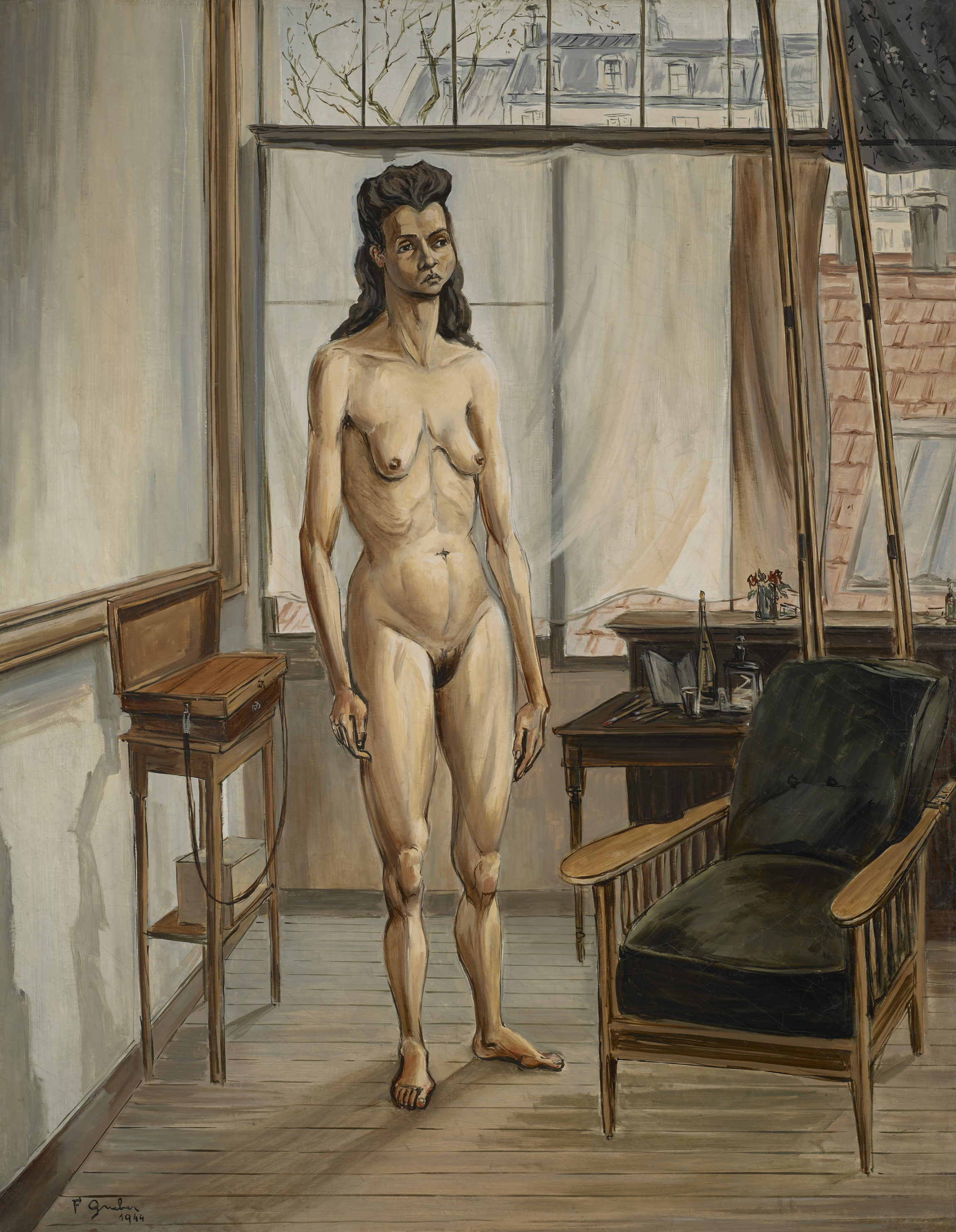

In 1944, the fate of Paris still hung on the uncertain outcome of the Second World War. That year, Francis Gruber painted his favourite model, Étiennette, standing naked with her arms hanging limply by her sides, thin, perhaps weakened by food shortages. Her skin is stretched taut over the muscles and bones of a body stripped of its sensuality. Her gaze is vacant, her mouth downturned. The space she stands in, powerfully structured by the walls, skirting boards, floorboards and window struts, is oppressive, trapping her in a clutter of cheap furniture that in turn seems frozen by her own immobility. The multi-directional vanishing points and off-kilter proportions heighten the feeling of discomfort, along with the harsh light, dry, fluid paint, dark, drab colours, chilly harmonies, and the dry, hard brushstrokes.

Time stands still in the artist’s studio that is part still life, part desolate landscape. The curtains drawn over the windows force us to confront the reality of a female body that is simply there, exposed. The motionless body that could almost be a shop dummy, the unrealistic space, and the significance of the void all nod to Giorgio de Chirico’s metaphysical realm, though without its atemporality and anxious, nostalgic ambience. The work’s underlying, restrained sense of violence is typical of new objectivist painting, but Gruber has refused its chilly, mechanical approach.

Gruber’s painting is both a private and a public undertaking by a man physically unsuited to battle and an artist who believed in art’s social utility. In both cases, the work is firmly anchored in the artist’s present reality and the harshness of human existence.