Bibliography

Itzhak Goldberg et Arnulf, Rainer, Arnulf Rainer. Visages dérobés, exh. cat. Paris, Galerie Lelong, 1996 (coll. Repères – Cahiers d’art contemporains n. 132): 38-[42].

Erika Billeter (ed.), Chefs-d’œuvre du Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts, Lausanne. Regards sur 150 tableaux, Lausanne, Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts, 1989.

Erika Billeter (ed.), L’autoportrait à l’âge de la photographie: peintres et photographes en dialogue avec leur propre image/Das Selbstportrait im Zeitalter der Photographie: Maler und Photographen im Dialog mit sich selbst, exh. cat. Lausanne, Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts, 1985.

![Arnulf Rainer, Ohne Titel (Face Farces) [Untitled (Face Farces)], 1969](https://www.mcba.ch/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/1984-050_RAINER_num4000_em-2304x2739.jpg)

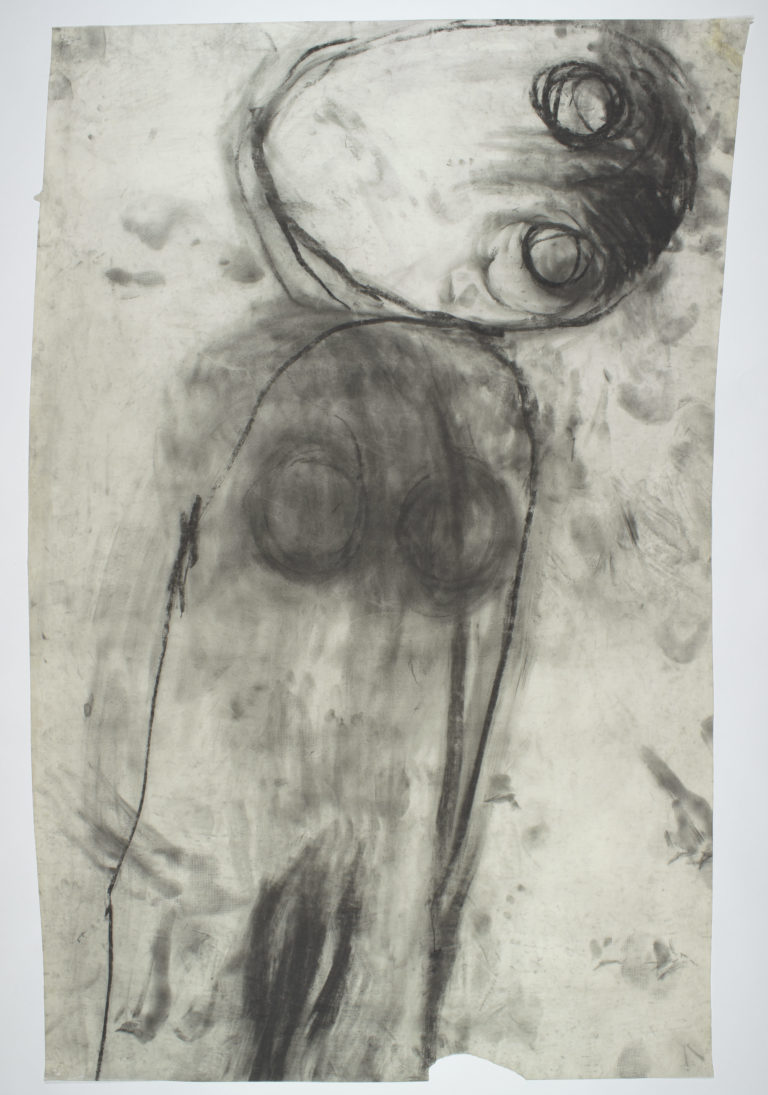

Arnulf Rainer created the first of his Übermalungen (overpaintings) in 1952, covering reproductions of art works with paint; to the point of making them in part unrecognisable. He painted over his own canvases and attacked his own face with the same energy in Face Farces (1969–75), a series of self-portraits based on photo booth head shots enlarged and touched up with paint.

The photographs, in which he stares at the camera while pulling a face or pouting, are energetically slashed over with paint. Rainer is interested in depictions of madness. The series is also heir to the Northern school tradition of the series of modified, expressive self-portraits, from Rembrandt’s successive changes to his own engraved portraits to Franz Xaver Messerschmidt’s ‘character heads’.

Rainer disfigures himself doubly. First, he sits for the camera without seeking a flattering pose. He explores the resources of bodily communication by adopting the most absurd facial expressions, simultaneously contorting various parts of his face: the resulting expressions are disconcerting in terms of meaning and are not particularly pleasant to look at. Rainer then adds to the work by hand, as in this case, daubing black and blue acrylic over his own face. Rather than destroying the work’s legibility, he brings in a note of tension between himself and the viewer who is confronted with his odd attitude.

Facing a man whose individuality is denied triggers a certain discomfort in the viewer. The artist’s intervention on the photograph echoes a taboo and an iconoclastic act: the handwritten inscriptions on the lower part of the photograph – signature, date and place on the negative – temper the action somewhat by foregrounding its place within the artistic process and affirming Rainer’s identity through his name. The work is located in the context of the Viennese actionists who recorded their own performances in photography and made their own bodies a surface for painting.