Bibliography

Catherine Grenier, Christian Boltanski: il y a une histoire…, Paris, Flammarion, Paris, Centre national des arts plastiques, 2010.

Jörg Zutter and Raymond Farquet, Christian Boltanski. Les Suisses morts: liste des Suisses morts dans le canton du Valais en 1991, exh. cat. Lausanne, Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts, Vevey, Éditions de l’Aire, 1993.

Günter Metken, Christian Boltanski. Les Suisses morts. Memento mori und Schattenspiel, Francfort-sur-le-Main, Museum für Moderne Kunst, 1991.

Christian Boltanski was a painter before turning to photography and film. He is renowned for his installations that are part inventory, part archive, exploring our relationship with history and memory, particularly what he refers to as the ‘small memory’ meaning ‘the opposite of the great memory found in books’. Born during the Second World War to a Catholic-born mother and a converted Jewish doctor who spent two years hiding from the Gestapo under the floorboards of the family apartment, Boltanski has constantly returned to the history that left its inexorable mark on his own life, that of his family and millions of other people.

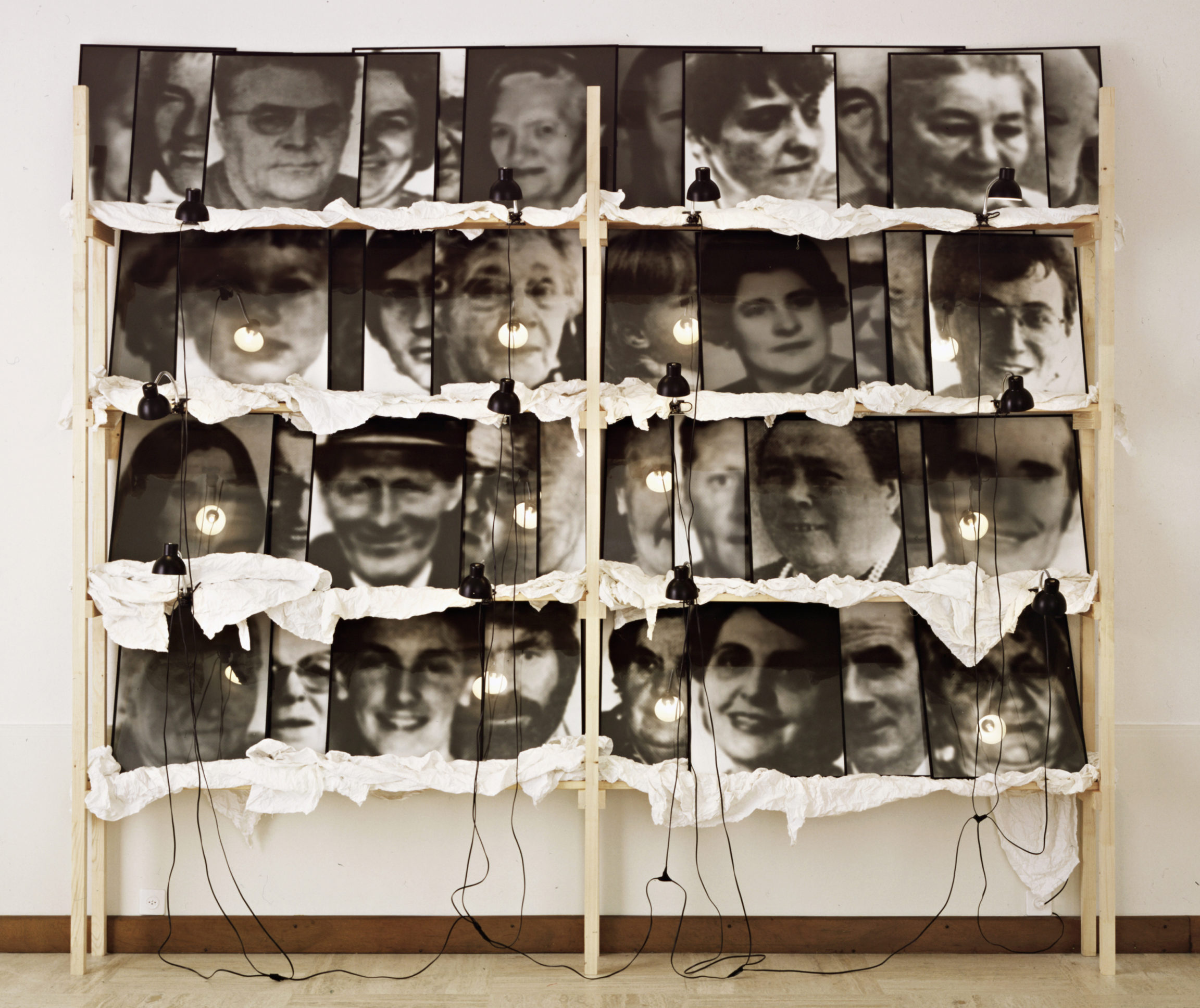

He first openly broached the Holocaust in the installation Les Archives at documenta 8 in Kassel in 1987, raising the question of the individual and the mass, the one and the multiple. The installation Réserve des Suisses morts builds on this work. It consists of a series of photographs of faces taken from death notices in the Valais newspaper Le Nouvelliste, re-photographed and enlarged before being arranged on shelves as nameless portraits that are deliberately stripped of any historical frame of reference. The images include portraits of living people cut out of the same newspaper, undercutting the narrative of death. The lighting and the sheets on which the photographs are arranged give the character of a memorial or an altar to these individuals. While Boltanski has defined Les Suisses morts as a work on the Holocaust, the use of portraits of Swiss men and women, who, as the artist points out, had no history-driven reason to die, allows him to explore the issue without taking up any particular stance in terms of historical representation or memorialisation. ‘Working on dead Swiss men and women raises the question, “why the Swiss?”. That’s what I’m interested in. The Swiss also die, because they are human.’