Bibliography

Olivier Mottaz, ‘Charles Blanc-Gatti, d’un futurisme tranquille,’ in Philippe Junod and Sylvie Wuhrmann (eds.), De l’archet au pinceau. Rencontres entre musique et arts visuels en Suisse romande, Lausanne, Payot, 1996: 153-167.

Arnauld Pierre, ‘La “musique des couleurs au cinéma”. Chromophonie de Charles Blanc-Gatti,’ Les Cahiers du Musée national d’art moderne, n. 94, Winter 2005/2006: 53-71.

In 1911 Charles Blanc-Gatti moved to Paris, then in a state of artistic effervescence, where he worked as a draughtsman. After a period working in fashion in Lausanne between 1919 and 1922, the Swiss artist came back to the French capital and developed an interest in musicalism, the modern theory concerning the equivalences of sensation and value between painting and music. Initiated by the Frenchman Henry Valensi, stimulated by the progress of physics and experimental psychology, musicalism continued from the nineteenth-century interest in synaesthesia, the analogies between differential perceptions explored by Charles Baudelaire in his poem Correspondances (1857).

In 1931 the musicalists formed an association. Blanc-Gatti, a founding member, published a manifesto with Valensi, Gustave Bourgogne and Vito Stracquadaini in April 1932: ‘We state our awareness, here, that from the aesthetic point of view, the musical spirit dominates in our period and that, in order to continue to translate our life traditionally, “Art must musicalise itself”.’ Arguing for the dynamic transposition of music and the translation of aural morphology, the signatories stated that they wanted ‘to work in obedience to the laws of inspiration and composition in music’.

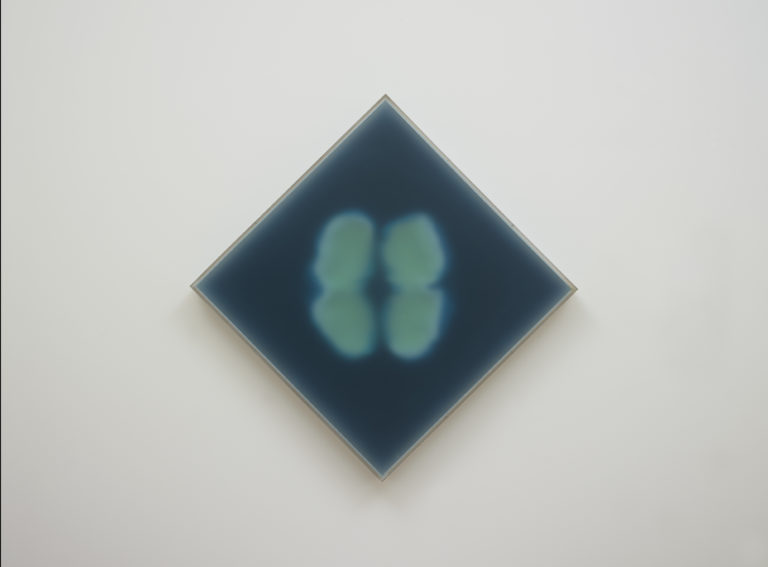

Blanc-Gatti sought to establish concordances between the vibrations of sound and light, to re-transcribe sound waves, their length, their frequency and their movement. He worked with the music of various composers, from Bach to Saint-Saëns and Rimsky-Korsakov. Here, the painter has executed a pictorial interpretation of Debussy’s Suite bergamasque for piano (1905) – most probably its third movement, Clair de lune (Moonlight). In a gradation of blues, he deploys a repertoire of forms derived from the circle. Arabesques and undulating lines, spirals and scrolls follow, interweave and radiate.