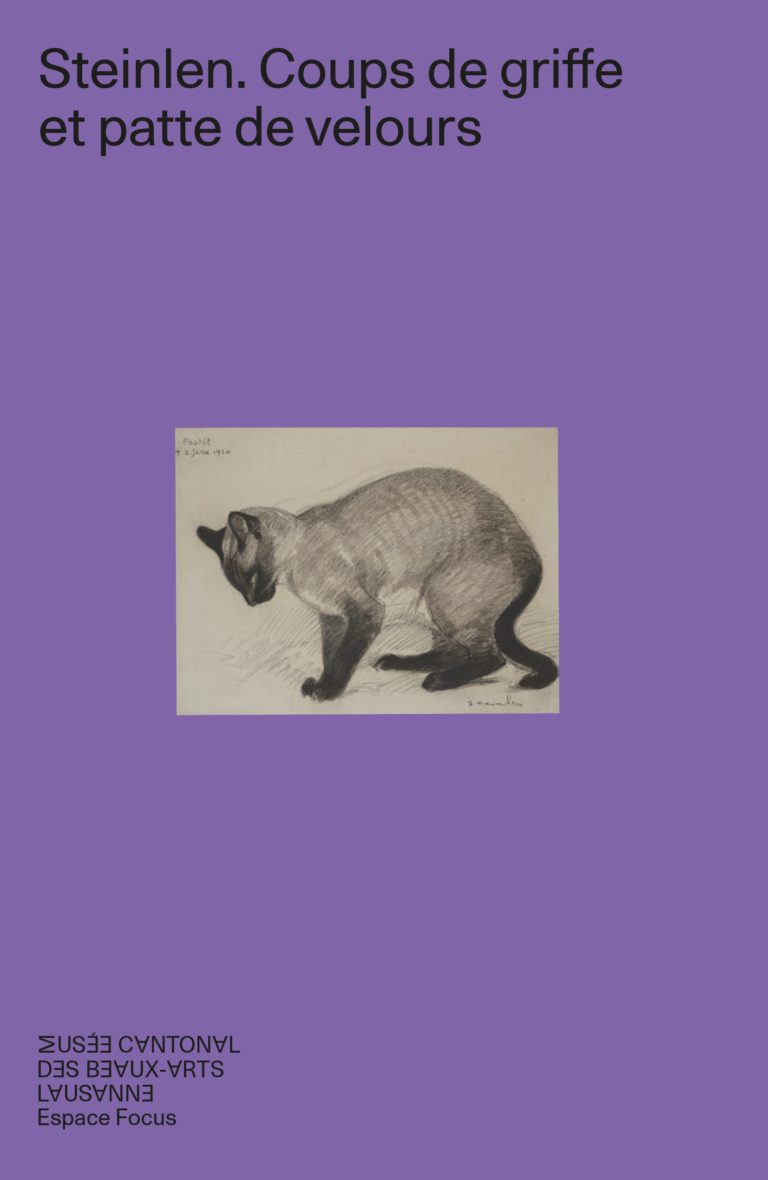

Exhibition guide Steinlen. Swipe of the Claws and Velvet Paws

22.9.2023 – 18.2.2024

Espace Focus

Born in Lausanne, Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen (1859-1923) settled in Montmartre in 1881, joining the artists of the literary cabaret Le Chat Noir and becoming the star draughtsman and illustrator of their publication. Observation directly from life, an art for deftly framing the composition, the gift of capturing movement… his droll scenes of the everyday soon were everywhere in Paris’s art periodicals and popular press. He made a name for himself as the premier chronicler of Paris’s Belle Époque.

Quick to decry injustice from an early age, Steinlen gladly put his art in the service of the struggle for a better society, ‘What good is preaching? You have to act. The world turns but not as it ought to…’ Stationed in the street, he observed the dire poverty of the common people and the corruption of the ruling class, which he roundly denounced by publishing his most virulent drawings in the anarcho-socialist press. At the end of his life, when the First World War broke out, he devoted shattering prints to the fate of civilians and soldiers.

Dealing directly with what was happening all around him, Steinlen was also the bard of the intimate scene in the tradition of Realist and Impressionist artists. He was a self-taught printmaker, painter and sculptor, and his independent output drew inspiration from his family, his sitters and models, and his cats. His work reveals the empathy that was natural to his character and his spontaneous embrace of life in all its manifestations.

Steinlen. Swipe of the Paws and Velvet Claws features for the first time a selection of works from the donation of the Zurich couple Paul and Tina Stohler, both fervent admirers of the artist. The show creates a dialogue between this large group of pieces and the MCBA’s Collection.

Steinlen passed away a century ago this year, but his talent as a draughtsman still dazzles. He awakens the conscience and touches the heart, then as now.

Biography

1859

On 10 November, in Lausanne, Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen, is born. He is the first of five children, son of a postal clerk and a housewife. His grandfather and paternal uncle are artists living in Vevey, illustrators for the famous almanac Le Messager boiteux.

1881

After graduating from high school in Lausanne with the traditional Latin and Greek education, he opts for a career in art. He leaves for Mulhouse to learn ornamental design for textiles, then at the age of 22, goes to Paris and settles in Montmartre.

1884

He joins the circle of artists (Signac, Forain, Toulouse-Lautrec, Vallotton), writers (Goudeau, Allais, Renard, Verlaine), and songwriters (Bruant) who staff Le Chat Noir. Starting in 1884, he begins publishing his drawings without words in the review put out by the art cabaret, soon becoming one of their star illustrators.

1885

Aristide Bruant opens his cabaret, Le Mirliton, and launches an eponymous journal, with a first-page illustration by Steinlen, who signs his work Jean Caillou.

1888

Birth of Colette, Steinlen’s daughter with his partner, Émilie Mey; she is one of his favourite models in her infancy and early childhood.

1891

He begins what will be a nearly ten year collaboration with Gil Blas illustré, furnishing the periodical with a dozen drawings each month.

1893

He makes his mark in poster art, becoming one of the great modern poster designers. The same year he begins drawing under the artist’s name Petit Pierre for the anarcho-syndicalist weekly Le Chambard socialiste.

1894

Success crowns Steinlen’s first solo show at the gallery La Bodinière, where he exhibits 300 works.

1897

Steinlen is introduced to Zola and Anatole France, and meets Jaurès and Séverine. He is an active contributor to La Feuille, regularly illustrating the anarchist-socialist review.

1898

On 13 January, Zola publishes J’accuse; Steinlen sides with France’s Dreyfusards. A past master in lithography, he learns engraving, in particular etching. Times are hard and Steinlen suffers from serious depression. His more private work takes on greater importance.

1900

A prolific illustrator for Paris’s booksellers, he puts much time and energy into artist’s books and works with the art publisher Édouard Pelletan (L’Almanach du Bibliophile pour l’année 1900, Anatole France’s L’Affaire Crainquebille, Jehan Rictus’s Les Soliloques du Pauvre).

1901

He becomes a naturalised French citizen. He begins his collaboration with L’Assiette au beurre, producing three thematic issues for the anti-establishment periodical.

1903

Unable to study at the École des Beaux-Arts for lack of funds, he nevertheless devoted himself, as a self-taught painter, to the medium as soon as he settled in Paris, following in the footsteps of the realists Daumier and Millet, and the Impressionists Manet and Degas. A major retrospective mounted in Paris (over 100 items) allows him to exhibit an important selection of his paintings; it is at this time that MCBA acquires two of his oil paintings, Fortifs (1886) and L’aurore (1903, currently hanging in the permanent-collection galleries of the museum).

1904

He draws closer to the circles that support a revolution in Russia.

1905

At the Salon de la Société nationale des beaux-arts, he shows his sculptures for the first time.

1906

First stays in Jouy-le-Moutier (Val-d’Oise), where he will acquire a country house.

1909

At the Salon d’Automne, an entire gallery is devoted to his work in illustration.

1911

Following the death of his wife, Émilie, his household is kept by Masséida, an African-born model and later housekeeper. He will make her one of his heirs.

1913

Publication of the Catalogue de l’œuvre gravé et lithographié de Steinlen, established by his friend Ernest de Crauzat (745 entries).

1914 – 1918

During the First World War, Steinlen, a pacifist, puts his talent as a draughtsman to work for simple soldiers, displaced populations, and civilians behind the front. In May and July of 1915, he visits the battle fields of the Somme, and later, in August 1916, the Marne, and finally in April 1917, Châlons-sur-Marne, as part of the “Missions artistiques aux armées” (Artistic Mission to the Armies). During the conflict, he creates numerous posters and prints, his war output.

1923

At the end of his life, Steinlen suffers from numerous episodes of depression. On 13 December, he passes away from a heart attack at the age of 64.

1970

MCBA mounts a retrospective, Steinlen, which will also travel to the Palais de beaux-arts in Charleroi and the Kunsthalle of Basel.

2008

MCBA mounts a second retrospective of the artist, Steinlen. L’œil de la rue, which travels to the Musée d’Ixelles, in Brussels.

2023

MCBA conserves over 1 000 of Steinlen’s works. Begun with acquisitions made in the artist’s lifetime, this extensive group forms one of the pillars of the MCBA Collection. Moreover, it continues to grow, notably in 2008 when the Jacques Christophe Collection was acquired, and again in 2016, thanks to the Paul and Tina Stohler Donation.

The mercifulness of Steinlen’s heart by Louise Hervieu

“A year has gone by since that grey smoky December morning when there was only darkness and the heavens were no more, when the face of Kindness was veiled like the countenance of a widow, because the great and pure Steinlen had ceased to be.

He would not have accepted being rich when there are so many poor people. He had met Fortune with Lady Fame but had taken great care not to detain her. What a poor schemer that made him! and that will stand as one of his glories. Yet he never knew dire poverty.

He was a musketeer, his beard a neatly trimmed pointed ducktail. His figure was handsomely and sturdily cut, and, with heroic childlike eyes, he had a wonderful heart for loving, a proud soul for fighting, and the gifts of a drawing master.

How much love did he give and deserve? That is the reason why death found him young when it led him away at the age of 64. He possessed all the forms of nobility, including the nobility of his craft. So sharp, nothing could fool him save his heart.

Who will care for the poor man bent double or wilfully defiant? Who will paint the girls, innocent and guilty of sinful love? The brief youth that blooms too soon like a hurried spring and has no summer. Who will commiserate with the distress of mothers?

Who will celebrate the triumph of lovers, those who own the world, just the two of them… for as long as they love each other?

Steinlen was the narrator of the street, that river of life embanked by high houses which carries along pell-mell wrecks and hopes.

Steinlen was the specialist of the flower and animals, the cat animal and the Chat Noir.

His tenderness towards the weak was as strong as his loathing for the oppressor, but he remained an artist and not solely a righter of wrongs. All that he built had the possibility of life. The joints played their part, the architecture of the body, where our organs are lodged, was respected just like all the demands of the animal that lived, could dart out and follow the impulses of its heart and the turbulent orders of its passions.

Such was Steinlen in Gil Blas, Mirliton, L’Assiette au Beurre, the Steinlen of Crainquebille and Barabbas, of Soliloques and Vagabond.

To this bouquet of tributes may I join a few thoughts that have remained fresh beneath the fealty of tears? So many times he made his way down from Caulaincourt to the out-skirts where I lived to come and sit on a low nursing chair, level with my sickbed.

He wanted us to talk of flowers. I confessed I knew only roses, or else wild flowers. His next visit he arrived with his load of peonies, “Come now, missy, try to get acquainted with these. I made a long detour to fetch them from my shopgirl. That’s where they are the best, for I am going to tell you a secret. It is the florists who fashion their flowers!”

Or else we would speak of art, our admirations or preferences. I said that the best and the most impressive of those in the profession was the sign painter, perched atop his ladder, curly-haired and singing at the top of his voice! It is to him that we owe those inescapable upstrokes and down: Wines and delicacies. Butter, Eggs and Cream.

“There is better than that! There is the auto- mobile painter!” – “Oh! Steinlen, do tell.” – “Well then, one must picture him, firmly seated and holding between his fingers a brush loaded with vermillion or cadmium. And the wheel is in front of him with all its spokes like a dark star. Then, like Jehovah setting worlds spinning with a tap of his heel, he puts it in motion. Dizzily it turns and meets the brush, immobile in the painter’s hand. And it is the genesis of the ideal decorative line, the pride of the coach- builder and admiration of onlookers” – “Oh! Steinlen!” And weary, I would fall back on my pillows…

There were silences, too, during which I sensed he was mindful of his own illness, weighed down, his breathing troubled. But he didn’t want me to notice anything, such was his discretion around his ills, for it was he who wrote, “It is better to keep silent and remain in one’s little shack when one can bring to one’s friends neither joy nor comfort.”

And that last time when I begged him, “Stop making the long trip, you’re weary and it is I who wants to get well and go see you”, he pretended to grow quite angry, “No! Would you listen to her! Nattering on like mummy and daddy and none of it holding water. First of all, I shall come back if I wish and whenever I like.”

But he did not come back! And as long as the species lasts, because of Steinlen’s death, there will be an empty space in the hearts of the unfortunate.”