Exhibition leaflet Groupe CAYC. Buenos Aires-Lausanne

19.5.2023 – 27.8.2023

Espace Focus

During the 1970s and 1980s, two tirelessly productive individuals – Jorge Glusberg, the director of the Centro de Arte y Comunicación in Buenos Aires (CAYC), and René Berger, the director of the Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts of Lausanne (MCBA) – shared a desire to spread the word, beyond the shores of their respective continents, about avant-garde artists active in their regions. Thanks to their energy and commitment, and their work together, a number of shows featuring works by Swiss artists were mounted in Argentina’s capital, while conversely pieces by Latin American artists were seen in Lausanne, at a time when these two art scenes existed on the margins of international recognition.

In homage to this intercontinental dialogue over 40 years after it took shape in the galleries and on the walls of the two directors’ institutions, the exhibition Groupe CAYC. Buenos Aires-Lausanne brings together artworks that once were traveling between the two continents. The show unites two outlying art scenes that developed in parallel, although they were molded by contrasting political, social and historical contexts. The artworks that emerged from those separate yet connected realities testify to a set of considerations that are quite different by necessity. While Argentinian artists were articulating a social discourse, the Swiss were taken up with formal concerns. The exhibition tracks then two narratives, which were briefly entangled in the margins of art history.

CAYC, Buenos Aires

In 1968, the Argentinian Jorge Glusberg, business owner, critic, curator, and artist, founded CAYC in Buenos Aires. Financed entirely by his personal fortune, this interdisciplinary center helped to promote different experimental practices starting in the 1970s, and it did so despite a political context in Argentina that was stamped and scarred by two dictatorships (1966-1973 and 1976-1983). A hyperactive and highhanded director, Glusberg put together a vast network of Argentinian and more broadly South American avant-garde artists with the idea of integrating it in the Western art market. Moreover, inspired by an import-export principle, he brought in art shows to Buenos Aires and mounted displays of works by South American artists at the CAYC venue and in foreign institutions. Works produced by the artists of the Grupo de los Trece (“The Group of Thirteen”), a collective associated with CAYC, were the ones that traveled the most.

MCBA, Lausanne

René Berger was the director at the time of MCBA, which was then located at the Palais de Rumine, but he also played a role in CAYC activities. He himself was already showing the results of avant-garde practices in his museum. He met Jorge Glusberg at the start of the 1970s and the two men were to exchange several exhibition projects. Swiss artists, for instance, were featured in Buenos Aires (Cinco artistas suizos, 1979; Félix Vallotton: el nabí suizo, 1980), while the Grupo de los Trece exhibited in Lausanne in 1981 (Groupe CAYC: dialogue avec l’Amérique latine). The works by Argentinian artists brought together in this gallery were all shown in the 1981 exhibition. Transported to Lausanne in suitcases, they were forgotten once the exhibition closed and only discovered when preparations were underway to move the MCBA collection to its present location in 2018. They form the core of the present show.

Video art in French-speaking Switzerland

In the 1970s, Lausanne was an important creative center for video art and Berger an active supporter of the new medium. He exhibited it in his museum and promoted it at international events, notably the various International Open Encounters on Video which were mounted by CAYC in Eastern and Western Europe and Latin America. Berger featured works by Swiss artists at these events; four of them are shown here.

Presented in 1977, Jean Otth’s Le Portillon de Dürer (1976) is part of the Vidéo-miroir series in which the artist uses closed-circuit technology. The production, recording and perception of the images are concurrent and present on the image being broadcast. Otth placed a mirror in front of the camera and then recorded his own hand drawing on the reflective surface. We see there the female model, placed outside the field of view captured by the camera, an image of which is equally visible in the playback screen.

In Cross Talks (1977), Janos Urban contrasts two timelines. The right side of the screen features excerpts of television programs while the left displays the image of the surface of a stretch of water. The border between the two registers is constantly shifting. Urban assembles a number of snapshots to compare different perceptions of time, i.e., contemplative time, which the water’s wavelets inspire; and the other, frenzied time of TV programs.

Heirs to the Fluxus legacy, the Genevan artists Gérald Minkoff and Muriel Olesen worked together as a couple. Music, rhythm, and humor predominate in their video pieces. Olesen, for instance, films herself in Basic music (sic) (1974) playing the tune Frère Jacques by plucking rubber bands with her teeth. She incorporates the accidental in her score and sings out loud the called for note when a rubber band breaks. In Minkoff’s Chalk Walk (1974), the rhythm is generated by the artist’s pacing up and down in a room while dragging the camera along with him.

Cinco artistas suizos

The first show Berger mounted for CAYC was Cinco artistas suizos, which opened in Buenos Aires in late 1979. The exhibition featured works by Silvie and Chérif Defraoui, Jean Lecoultre, Gérald Ducimetière, and Juan Martínez, all artists who were close to MCBA.

An antimilitarist, Juan Martínez denounced in his work Franco’s dictatorship, which held his native Spain in its grip until 1975. Here he creates a character on a human scale whose senses, particularly sight, are covered by a sheet, a metaphor of voluntary blindness. Over the white cloth covering this individual, the shadows of armed figures play. The comfort of inaction is associated with cowardice.

Formalism goes to the heart of Gérald Ducimetière’s focus as an artist. In the series on display, he superimposes dried flowers over photography of museum galleries that are empty save for a lone bouquet of flowers. Juxtaposing different codified realities of the same motif – here photographic and physical – was then one of the features and focuses of Conceptual Art.

In 1980, engravings by Félix Vallotton were exhibited at CAYC in Buenos Aires. Unlike Cinco artistas suizos, this event proved a great success with the public.

Jorge Glusberg and Arte de sistemas

In Argentina, the regime became more repressive starting in 1968, the same year that CAYC was founded. Aware of the dangers and risks of censorship, Glusberg decided to exhibit a “metaphorical” art rather than a political one. And to lend a certain coherence to CAYC’s course of action, he came up with a theoretical guiding principle he called “arte de sistemas”. Inspired by “Systems Esthetics,” an article that Jack Burnham published in 1968 in Artforum (shown in the display case), this approach stressed the social context in the production of artworks. The Grupo de los Trece, the artists collective that created most of the works exhibited at CAYC, adhered to Glusberg’s principle and steered clear of any kind of militancy. The group mainly produced artworks whose ostensible subject matter came from nature, history, mythology, and ecology. In 1977, the group turned its attention to the balance between the natural and artificial worlds, and especially agriculture’s impact on landscapes, species, and peoples, postwar Argentina having adopted a policy of mass production under the twin banners of improved output and export.

Jorge González Mir and Vicente Marotta

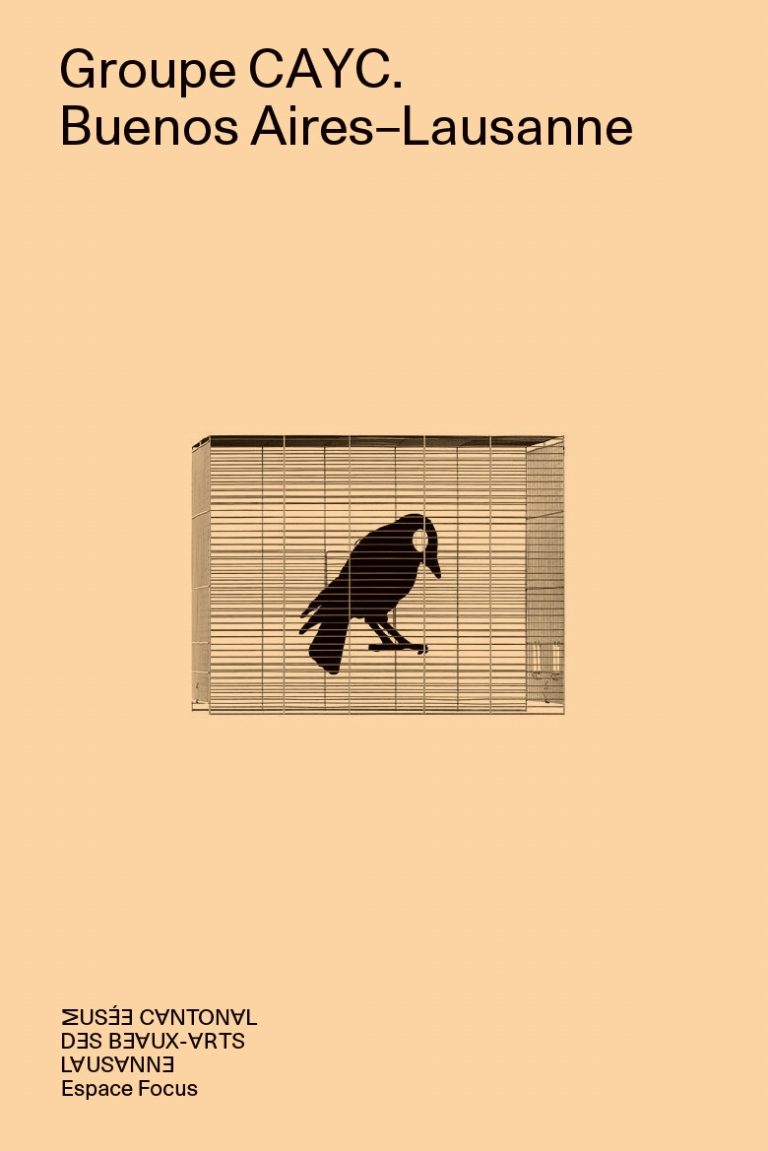

Made up of industrial cages hanging from the ceiling and containing fake bird images, Jorge González Mir’s installation Factor interespecífico (1977) offers a contrast between the sham and the real. The piece can be read as a condemnation of the domestication of nature, the erasing of the connection between humans and their environment, and a reflection on the concepts of freedom and imprisonment.

In his work, Vicente Marotta tackles questions of mass production, food, and the unequal division of food resources. In the late 1970s, he fashioned foods, tools and shoes from sandstone. In Man’s Traces and Man’s Footsteps (1970-1980), Marotta plays with the ideas of artifice and reality, emphasizing hands and feet. While the tool handles are indeed real and show traces of cast hands, the shoes are not. Once solidified, these objects lose their dimension as things that can be used, becoming akin to fossils or museum artifacts.

Luis Fernando Benedit and Víctor Grippo

In the late 1970s, Luis Fernando Benedit developed his series of Cajas (“Boxes”), which looked at the industrialization of agriculture in Argentina, one of the main sources of the country’s wealth. Caja Semen (“Box-Semen”) refers to the question of artificial insemination and genetic modification of animals bred for slaughter in terms of improved yields. Here a box symbolically holds the semen of a bull represented by a framed photograph.

Víctor Grippo began his series of artwork-drawers in 1979. At the time the artist showed a deep interest in alchemy and the processes by which matter is transformed. Several of his drawers, for instance, holding various objects, were subjected to mercury-and lead-based chemical processes, reflecting the disheartening confusion of a world that favors science more than conscience in the race to achieve greater progress. Grippo thus offers the eye objects suffused with poetry and nostalgia, as in this image of a slightly faded rose in industrial gray.

Jacques Bedel and Leopoldo Maler

Trained as an achitect, Jacques Bedel explores the symbolic power of books as cultural objects. In place of words, his books contain archeological reliefs, based on landscapes all over Argentina’s territory, lands that are in the midst of great change. The artist references that territory and attempts to preserve it through casts, recreating fossilizations, charring, using metals, clays, and other materials. These “cities of silver” seem to be in ruins and belong to an abstract time.

Leopoldo Maler was a late-comer to the Grupo de los Trece, only joining the collective in 1977, following several years in London. In his work, Maler gives voice to his interest in the human body and movement, although always with a fateful or disastrous dimension that recalls the temporary nature of life. This is the case in Critical Eye (1980). Trapped in an adjustable wrench by a rivet, an eyeball figures an arc of a circle against a black background, introducing a performative aspect to the artwork as well as an ambivalence. Who or what, the work of art or the viewer, is observing the other?