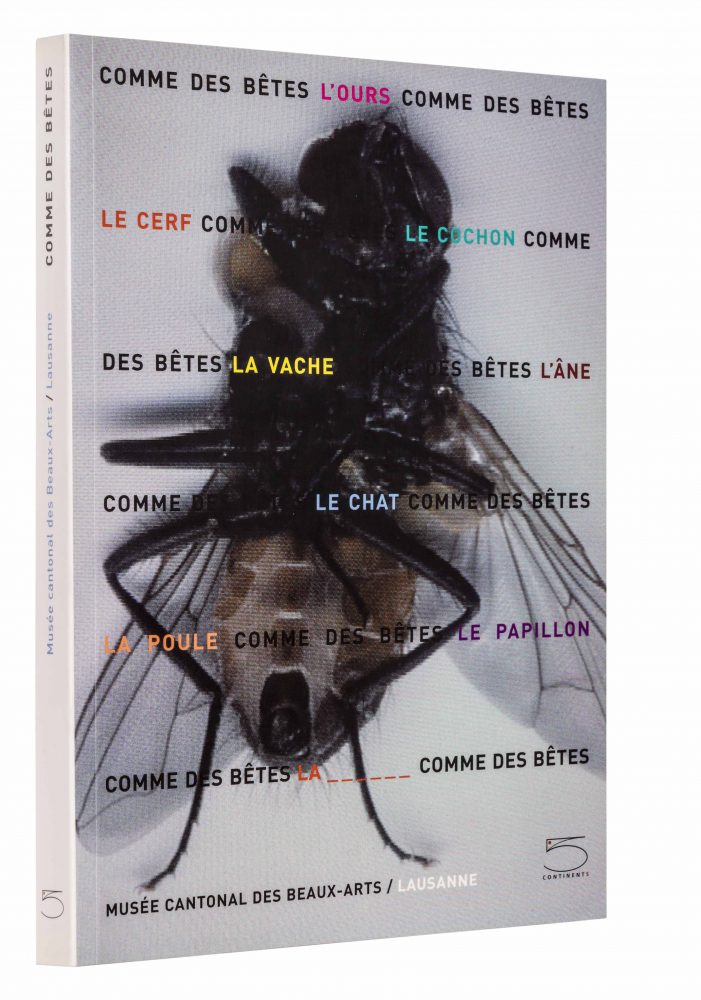

Comme des bêtes (Like beasts) Bear, cat, pig & co.

As its starting point the exhibition takes nine emblematic animals – the bear, the stag, the pig, the cow, the donkey, the cat, the hen, the butterfly and the fly –, animals that are “close” to us (whether we want them to be or not), offering a range of images that are now commonplace, now surprising or even spectacular, all of them clues to understanding human beings’ complex relations to animals.

“Comme des bêtes” shows us that the depiction of animals operates across the ages and civilisations as revelatory of our states of mind, our desires, our worries, our imagination, our (natural or pathological) needs for contact with animals or for keeping them at a distance. For we are speaking of ourselves when we speak about animals, we show them through our eyes when we depict them: “[the narrative] features [animals], it is true, but as representatives of the human race”.

Whether tame or wild, useful or purely harmful, sublime or grotesque, triumphant or tragic, as depicted by artists the bear, the pig, the cat and the others are fascinating mediators in our relations with nature. For animals often act as intermediaries or even intercessors : “[…] animals above all allow an expansion of contact with the natural world of which so many individuals in an urban setting are seriously deprived. In return for being cared for and fed, they have been conditioned to respond to human beings’ expectations, a real ‘compromise’ between them and things. Amidst isolated and maladjusted human beings often incapable of loving, the animal lover achieves a blessed equilibrium.” Images of animals – whether positive or negative – always end up by turning against us, insistently asking us: what is a human being? A classic philosophical question. What is an animal? A biological question. However, “The animal is not just an organism of biological interest; it also refers back to a figure of otherness in relation to which man defines his specific identity.” What does “animality” or “bestiality” mean? An ethical question. What links human beings and animals? A question touching on ethology, ecology, biogenetics and phylogenesis. And above all what differentiates human beings from animals? A question to which we expect reassuring answers (the philosophers offer some): according to Descartes it is reason; according to others consciousness, language or the soul; according to Rousseau, freedom of choice. In Part I of his Discours sur s’origine et les fondements de l’inégalité parmi les hommes (1755) he writes: “Some philosophers have even suggested that there is more difference between this man and that man than between this man and this beast; so it is not so much understanding that makes man specifically distinct among animals as his quality as a free agent. Nature issues commands to all animals, and the beast obeys. Man feels the same impression, but he recognizes that he is free to acquiesce or resist; and it is primarily in consciousness of that freedom that the spirituality of his soul is manifested: for physics in a way explains the mechanism of the senses and the formation of ideas; but in the power to wish or rather to choose and in feeling that power, only purely spiritual acts are found, and nothing of them is explained by the laws of mechanics.” As Giorgio Agamben sees it, what defines man is his consciousness of what differentiates him from animals: “man is the animal who has to recognize that he is human in order to be so” or who “recognizes that he is not”. Jean-Christophe Bailly adopts a completely different point of view, based on a shared destiny of living creatures, on the animal constant within which man is only an epiphenomenon. He engages in a philosophical exercise consisting of thinking of animals as something that exists outside man, his thought, language, and world.

The works and the artists

“Comme des bêtes” brings together works – paintings, sculptures, photographs, videos, installations – from the 17th century to the present, coming from those held by the musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne and many public and private collections. The artists represented include: Gilles Aillaud, Johannes Alder, Luc Andrié, Albert Anker, René Auberjonois, Bai Yiluo, Stephan Balkenhol, Balthus, Auguste Baud-Bovy, Pascal Bernier, Julien Berthier, Ernest Biéler, François Bocion, Pierre Bonnard, Marius Borgeaud, Eugène Boudin, Elias van den Broeck, Frank Buchser, Balthasar Burkhard, Eugène Burnand, Marguerite Burnat-Provins, Robert Calpini, Cao Jinping, Valentin Carron, Leo Copers, Philibert-Léon Couturier, Liz Craft, Wim Delvoye, Gérard Deschamps, François Desportes, Robert Devriendt, Mark Dion, Duan Jianwei, Duan Jianyu, Duan Zhengqu, Balthasar Anton Dunker, Franz Elmiger, Slawomir Elsner, Ralph Fleck, Ceal Floyer, Pierre-Philippe Freymond, Gloria Friedmann, Andrea Gabutti, Marguerite Gérard, Jean-Marie Gheerardijn, Francisco Goya, Arti Grabowski, J. J. Grandville, Barthélémy Guillibaud, Alexander Hahn, Eberhard Havekost, Ferdinand Hodler, huber.huber, Rodolphe Huguet, Luzia Hürzeler, Richard Jackson, Louis-Godefroy Jadin, Ji Dachun, Alexandre Joly, François Jouvenet, Ilya Kabakov, Bharti Kher, Thomas Kitzinger, Pierre Klossowski, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Hans Krüsi, Batholomäus Lämmler, André Lasserre, Liu Wei, Liu Xiaodong, Albert Lugardon, Luo Brothers, Paul McCarthy, Naofumi Maruyama, Ana Mendieta, Gottfried Mind, Katharina Moessinger, Jean-Bloé Niestlé, Eugène Normandin, Yoko Ono, Ulrike Palmbach, Paola Pivi, Eric Poitevin, Elodie Pong, Marjetica Potrč, Odilon Redon, Peter Regli, Georges Rey, Rembrandt van Rijn, Claudia Renna, Didier Rittener, Samuel Rousseau, Edouard Marcel Sandoz, Eugenio Santoro, Christoph Schmidberger, Carolee Schneemann, Friedrich Schröder-Sonnenstern, Francisco Sierra, Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen, Erick Swenson, Rodolphe Töpffer, Constantin Troyon, Félix Vallotton, Not Vital, Mark Wallinger, Andy Warhol, Stephen Wilks, Xu Bing, Xu Zhen, Yang Zhenzhong, Zhao Bandi