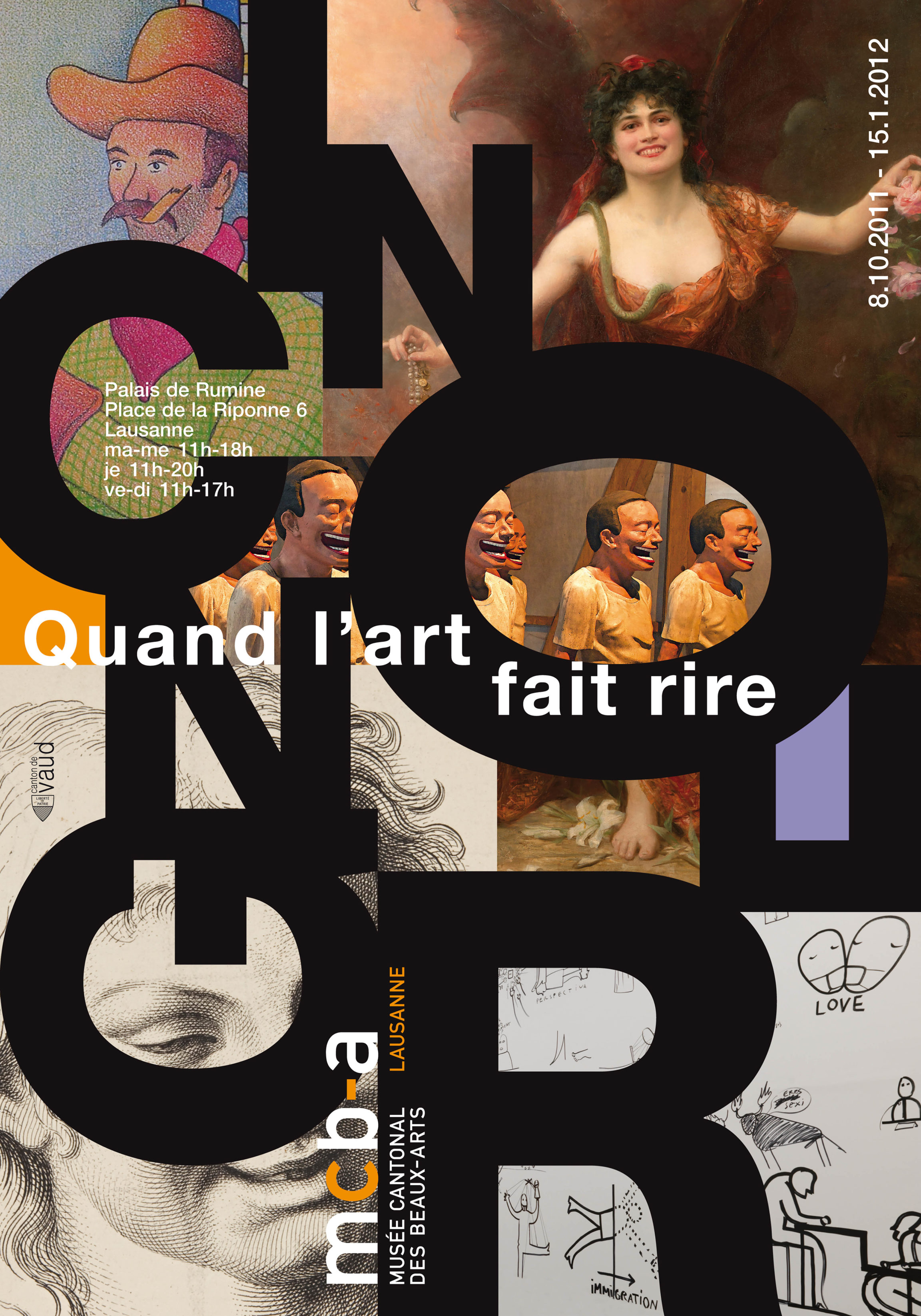

Incongru

Quand l’art fait rire

Art is a serious business. Artists do not poke fun at their clients, whoever they may be – emperors, kings, princes, ambassadors, private individuals or art dealers – unless they know it will be taken well. The creed of the bourgeoisie is based on reason and reasonable people are serious people.

Laughter, on the other hand, deforms the human face, it can become a weapon of diabolical seduction and a menace to propriety and the established order. Historically art has never made a good bedfellow for

laughter, humour and comedy. There is a basic incongruity between the two domains.

Of course there are domains in which laughter slots right in: comedy, satire, pastiche and burlesque. In the visual arts it has been confined to the grotesque and caricature, whereas the smile, belly laugh and subtle irony all find their way into artistic creation. Artists have always been as interested in

the physical aspect of laughter (the face as a mirror of the state of the soul) as in laughter as a release mechanism: most of the time it is in fact the result of a difference, a paradox, a variance – an incongruity.

In the seventeenth century, humour became a tool which the artist used for purposes of criticism, contestation and subversion, and which he applied inside the art system or brandished in the direction of society with its standards and conventions, its consensus, morality, harmony and order. Around 1900 derision was employed as a safeguard against the absurdity of existence and horrors of war, and later as a defence against all sorts of totalitarian regimes, including that of the late-twentieth-century “panludisme festif” (Georges Minois). But will the spirit of amusement, incessant fun, standardized and programmable laughter, and generalized derision bring about the “death of laughter”?