Visitors guide

The Collection

Visitors guide

The Collection

To see here what cannot be seen elsewhere! This is the guiding spirit behind this hanging of the MCBA’s collection. Since 1816, acquisitions, gifts, bequests and deposits have constantly enriched this collection. It allows visitors an opportunity to more fully appreciate the work of artists from the canton of Vaud and French‑speaking Switzerland more generally, whether they pursued their careers at home or abroad, and to compare and contrast it with international art trends.

The collection is especially strong in relation to movements such as Neo‑Classicism, Academicism, Realism, Symbolism and Post‑Impressionism; abstract painting in Europe and the U.S.; Swiss and international video art; New Figuration; Geometric Abstraction; and, in every period, the work of socially and politically engaged artists. It also comprises major monographic collections, including work by Charles Gleyre, Félix Vallotton, Louis Soutter, Pierre Soulages and Giuseppe Penone.

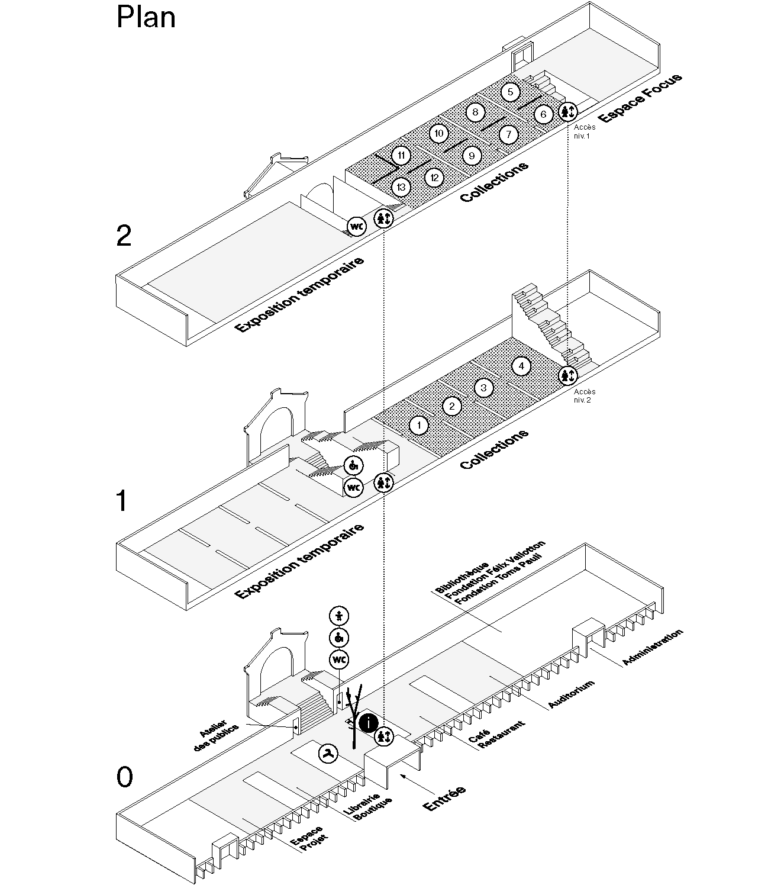

Installed on two levels, the selection from the permanent collection changes regularly, and pieces from the MCBA’s holdings are brought into dialogue with work on loan from private collections. In this way, our view of the astounding vitality of art as seen from Lausanne is always renewed.

1st floor

Room 1

The road to modernity

Colonialism and Humanism

Starting in the Renaissance, European expansion overseas fundamentally altered the way the world was depicted. Their imaginations fired by tales of exotic travel and the many artistic goods coming

in from distant lands, European artists dreamed up works that show the allure of the exotic (The Concert tapestry) for them and their patrons. The Bible remained a major source of inspiration in history painting and its ambitious compositions done in quite large formats. Nevertheless, humanism offered a new, more naturalist interpretation that initially emphasised human beings and soon after their emotions. Following in Caravaggio’s giant footsteps, the Neapolitan School turned to the technique of chiaroscuro to dramatise the great moral subjects (ANDREA VACCARO, LUCA GIORDANO). Individual portraiture swept through the arts during the second half of the 17th century. In the France of Louis XIV, portrait painters also sought to realistically capture the physical appearance, social rank, and distinctive qualities of their sitters, whether bourgeois or noble (HYACINTHE RIGAUD).

Emigration

At the end of the 18th century, many Swiss artists emigrated to Paris or Italy, seeking to make a name for themselves in history painting. LOUIS DUCROS and JACQUES SABLET settled in Rome. Ineligible for religious art commissions (reserved for Catholics), they specialised in other genres, the former in large‑format views of ancient monuments and picturesque sites, and the latter in open‑air group portraits and popular scenes. A generation later, CHARLES GLEYRE, who had studied art in Paris and visited Rome, set out for a long eastward voyage that would take him to Greece and down the Nile. After his return to Paris, he devoted himself to classically inspired history painting in a singular style midway between Romantic passion and academic rigour. He also took up teaching; students at his studio included the future Impressionists Monet, Renoir and Sisley.

Landscapes

Starting in the late 18th century, highly meteorological landscape paintings expressed the anxiety prevalent during the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars. Catastrophe painting, full of storms and erupting volcanoes, as well as vast, desolate landscapes, contrasted human solitude with the sublime grandeur of nature (LOUIS DUCROS, CHARLES GLEYRE).

History painting

For Swiss artists, the great challenge resided in the invention of a history painting that would express their country’s spirit of independence and democratic ideals and help construct a modern national identity (JEAN-PIERRE SAINT-OURS, CHARLES GLEYRE).

Room 2

The triumph of realism

During the 19th century, Switzerland went through a step‑by‑step process that transformed it into a unified federal state. Since the country lacked a centralized art education system and a dynamic market, its artists often went abroad. Their unique qualities flourished in landscape and genre painting. Geneva’s FRANÇOIS DIDAY and ALEXANDRE CALAME were the founders of a truly Swiss art featuring its emblematic landscapes. Diday portrayed Alpine peaks, with a monumental and sublime vision still strongly infused with Romanticism. His student Calame, influenced by 17th‑century Dutch painting, preferred middle altitude views. The triumph of realism in the second half of the 19th century, from Naturalism to Impressionism, allowed Swiss artists to shine at the Paris Salon. Their work tended to represent the traditions and customs of people living far from big cities, spared from the Industrial Revolution that dissolved traditional communities of farmers and craftsmen. EUGÈNE BURNAND and ERNST BIÉLER did animal painting and genre scenes in monumental formats previously reserved for history painting. FRÉDÉRIC ROUGE and ALBERT ANKER painted portraits of social and professional archetypes, while also looking to the world of children for inspiration. The Barbizon School and the long stays in Western Switzerland of Jean‑Baptiste Camille Corot and GUSTAVE COURBET (living in exile in La Tour‑de‑Peilz) greatly influenced a younger generation who turned toward intimate landscapes. A proponent of atmospheric plein‑air painting, FRANÇOIS BOCION took Lake Geneva as his main subject, tirelessly recording the play of sunlight on the water and the passing clouds above. After finishing his art studies in Paris, he spent the rest of his days in his native Lausanne, where he cultivated a local clientele. In the field of portraiture, Impressionism and Art Nouveau invited painters to represent quiet moments in natural surroundings or bourgeois drawing rooms. The act of painting became a moment of truth free from social conventions. Models were seen in informal poses, at rest or carrying out leisure activities and other daily pursuits (ERNST BIÉLER, LOUISE BRESLAU, CHARLES GIRON). Like the Belgian sculptor CONSTANTIN MEUNIER who realistically portrayed men labouring under harsh conditions, Switzerland’s THÉOPHILE-ALEXANDRE STEINLEN put his art at the service of his political convictions and his commitment to the struggle against social injustice. Making Montmartre his home, he chronicled the days and nights of the Parisian lower classes whose voice he became.

Room 3

From Post-Impressionism to the avant-garde

At the turn of the 20th century, the Impressionists gave way to a new generation of artists. A number of new styles and movements were to appear in this transitional period which set the stage for the advent of modernity.

Starting in the late 1880s, a decorative graphic style came to dominate the European art scene. Even in portraiture, the style favoured flattened representation, a synthesising spirit, and the stylisation of forms. Gustav Klimt in Austria and Ferdinand Hodler in Switzerland were sources of inspiration for large-scale compositions in which women are associated with nature (ERNEST BIÉLER, GUSTAVE BUCHET). At the same time, the Symbolists took refuge far from industrial modernity in dreams, the ideal, and spirituality (MAURICE DENIS). The ancient myths were a pretext for new epics whose heroes and heroines express the fragility of human beings (PLINIO NOMELLINI). Landscapes became mirrors of the soul and welcomed its projections (HANS SANDREUTER). A member of the Nabis’ circle in the 1890s, Félix Vallotton nonetheless kept his faith in realistic figuration when the post-Cézannian art scene was shifting to abstraction. He devoted the later part of his career to a severe and demanding exploration of traditional genres in painting, with a preference for portraiture, landscapes, and still lifes.

Following Ferdinand Hodler’s death in 1918, GIOVANNI GIACOMETTI and CUNO AMIET dominated the Swiss-German art scene. They were seen as the major representatives of a new expressive painting that claimed the primacy of colour as a principle of composition, doing so in the wake of Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. Settled far from the city, Giacometti and Amiet chose a life in harmony with their families and nature (the upper alpine valleys of the Engadin for the former and the countryside around Bern for the latter), subjects that the two artists tirelessly returned to in their portraits and landscapes. Twenty years their junior, the Swiss-French GUSTAVE BUCHET went up to Paris to be closer to the avant-garde movements and take in their innovations. Influenced by Cubism and Futurism in the 1910s and later Purism being promoted by Le Corbusier and Amédée Ozenfant during the interwar years, he eagerly sought new aesthetic solutions. In his painting and sculpture he developed a personal palette of forthright and muted colours, and strictly constructed and arranged compositions, using them to depict rhythm and movement.

Room 4

Figurative art, from Auguste Rodin to Alberto Giacometti

In the second half of the 19th century, AUGUSTE RODIN was the most remarkable champion of an approach to sculpture that was rapidly changing, between the classical tradition until then and modernity. For Rodin, a piece’s resemblance to the model had to be both physical and moral. His heirs, like ÉMILE-ANTOINE BOURDELLE, went a step further in expressiveness, working with notches, crevices, and mutilations; they integrated the pedestal or base into the overall design of the work’s volumes.

In the mid-1920s, ALBERTO GIACOMETTI distanced himself from Rodin’s legacy and what Bourdelle had taught him. He studied Cycladic and Egyptian art, discovered the art of Africa, Mexico and Oceania, and tapped into the principles of Cubism and later Surrealism. Concentrating on analysing his view alone, he pushed his decomposing and paring down of bodies to the limit.

In Geneva in late 1941, Giacometti renewed contact with BALTHUS, whom he had met in Paris in the 1930s. During the War and the following decade, many other artists who, like them, strongly felt the need to get back to what is human, rejected Abstraction and questioned once again figuration in the context of existentialism. In his portraits, Balthus explored a personal aesthetic based on effects achieved through disproportion, unusual poses, and formal simplifications.

A feeling of unease comes from the rigidity of the body’s position and the emptiness in the eyes that Balthus lends his subjects. That malaise is seen in the paintings done during the War by FRANCIS GRUBER, who took the hard reality of both the period and the human condition and translated it into cold light, gaunt bodies frozen in place, and oppressive spaces. At the same time, Giacometti was finding that capturing the physical and psychological traits of his subjects was a goal that could never be reached. Bringing sculpture down from its pedestal, he interrogated its connection with the viewer and space.

Slender or massive but always frontal in appearance, his figures seem like blocks of magma, shredded, kneaded, and gouged out. Looking for a new kind of figuration, JEAN DUBUFFET turned to simplifying his means to the extreme, opting for the rough line and clumsy unrefined drawing he admired in the work of self-taught artists. He, too, pursued a physical confrontation with paint, covering the canvas with thick pasty layers of putty-like pigments. In his landscapes, he was, like Balthus, searching for the ‘wall effect’ of fresco painting. ZAO WOU-KI arrived in Paris in 1948 and was to count Giacometti amongst the friends who provided him with support in his formalist search. Opting for lyrical abstraction as the way forward, he reconciled his cultural Chinese background with Western modernity, reconnecting with primordial gestures in large dynamic compositions.

2nd floor

Room 5

A more figural abstraction: the 1950s

The postwar period in both France and the United States saw new trends in abstract art quite different than the geometric approach of abstractionist pioneers such as Kasimir Malevitch, František Kupka, Piet Mondrian and Sonia Delaunay. Various labels such as “Lyrical Abstraction” and “Abstract Expressionism” were put forward, but none of them successfully embraced the diversity of these artists. For example, in Paris, MARIA HELENA VIEIRA DA SILVA made allusive paintings whose fragmented compositions sometimes suggested architectural forms, while PIERRE SOULAGES explored the effects of textures and light using a variety of tools, raw materials and supports. Europe also attracted American painters. In Italy, CY TWOMBLY developed an intimate and erudite abstraction steeped in references to antiquity. In Paris, BEAUFORD DELANEY was experimenting with the possibilities of a queer abstraction, both fluid and luminous. The impetus of the creative project itself finds expression in the freedom of the artist’s gesture, which goes as far as saturating the pictorial space, as KIMBER SMITH’s painting testifies.

Room 6

Escape from the canvas: 1960s – 1970s

In the late 1960s, the social revolution sweeping throughout Western Europe erupted in art‑making as well. Artists were eager to cast off the weight of tradition. Painting was the first medium to undergo this transformation as Pop Art made consumer society its subject, using vivid colours and slogans evoking the advertising signs per‑ meating the urban environment (JANNIS KOUNELLIS, ÉMILIENNE FARNY). In Paris, the Nouveau Réalisme artists (DANIEL SPOERRI, DIETER ROTH) embedded real‑life objects in their work. Others, inspired by the Fluxus movement, erased the boundaries between life and art. With a touch of humour, they absorbed everyday routines, images and objects into their work and appropriated industrial materials such as neon, phosphorous and plastic (TADEUSZ KANTOR, JANOS URBAN).

Video art emerged as a medium for visual and all sorts of experimentation as some artists turned their own bodies into a political statement (VALIE EXPORT), while others experimented with the medium itself (JEAN OTTH, NAM JUNE PAIK).

Room 7

Spaces of the body: 1980s

During the 1980s a new trend in painting and sculpture arose, a counter current to the austerity of the minimalist and conceptualist mouvements of the preceding decade. Neo Expressionism, instead, drew inspiration from earlier twentieth century art. Its avatars in Germany and Austria were the Neue Wilde (New Fauves); in Italy, the Transavanguardia; in the U.S., the Bad Painting artists. Called “figuration libre” in France, and appearing in Switzerland as well, this rough but often euphoric art was the product of a determined, violent attack on a surface, grappling with a quickly emerging image. Drawing and painting lost their distinctive attributes. Charcoal, ink, watercolours and acrylics were applied directly, often on paper, with no preliminary sketch, as in the work of MIRIAM CAHN, GÜNTER BRUS, and BIRGIT JÜRGENSSEN. The sheet of paper shows signs of the artists at work (crinkles and folds), their entire body engaged in an intense and immediate moment of creation. Although the body or a trace of it is clearly present, other artists make use of an altogether personal mythology to signify it. HÉLÈNE DELPRAT, for example, adopts a type of figuration that references totemic forms in her pictures from the 1980s, while ALBERT OEHLEN reappropriated motifs that are full of associations in a gestural painting that rejects any and all technical constraints.

Room 8

Abstractions

Once they are stripped of all reference to the exterior world, paintings are no longer about anything but their own forms and materiality. This is what OLIVIER MOSSET, in 1969, called “the degree zero of painting.” The absence of events is manifest in his large red monochrome done twenty years later. JOHN M ARMLEDER, associated with the Neo‑Geo movement, made what he called “furniture sculptures,” a droll reminder that the purpose of artworks is to decorate living rooms. The thinking of these two artists about the renewal of abstractionism encouraged a strong interest in geometric abstraction in the Lake Geneva region, beginning in the 1980s and continuing today. Instead of bearing the artist’s signature touch, the canvas is covered with a uniform application of paint; subjectivity, neutralized by geometrical forms, is evident almost only in the formal choices. While some artists allude to personal stories in their work (JEAN-LUC MANZ), others stick to a pre‑established protocol (CLAUDIA COMTE) or explore the painting as an object and the sculptural qualities of the surface (PIERRE KELLER).

Rooms 9 –10

Reclaiming the stage

Throughout history, many artistic positions have been marginalised or rendered invisible. This is particularly true of queer practices, which draw their political significance and aesthetic strength from the history of non‑normative communities, without constituting a stable, fixed category. On the contrary, by refusing to promote a normative system marked by binarity, the artists brought together in these rooms place the fluctuating and multifaceted nature of our identities at the heart of their thinking. Beyond their diversity, these forms of expressions are united by the same drive to regain visibility.

Often incorporating elements from the world of design, TOM BURR’s work focuses on the erosion of public areas and our status as viewers before a fantasised space. The two platforms look like theatrical spaces that are free of (re)presentations and demonstrations, like a set waiting to be activated. Humorously reappropriating the trompe‑l’oeil technique by including fragments of the body, SARAH MARGNETTI questions the political dimension of the domestic sphere and its architecture. The complex dynamics that exist between the individual and the collective, the private and the public, interior and exterior are at the heart of these strategies of visibility. Pierre Keller’s work in photography captures from life the erotic odyssey of the gay scene in the 1980s, which was marked by its underground reality. In contrast, fascinated by the mechanisms of celebrity and the images it generates, NINA CHILDRESS immortalises the androgynous figure of Swiss singer Patrick Juvet in a defiant pose that suggests self‑affirmation. Parodying the biopic genre, the performative element also gives substance to GUILLAUME PILET’s series of autobiographical drawings.

Finally, the practice of PAULINE BOUDRY / RENATE LORENZ is based on a “queer archaeology” that revives forgotten drag figures by superimposing images. The film Normal Work is inspired by archival photographs taken in England in the 1860s by Hannah Cullwick, who worked her entire life as a servant. She is seen posing in her work clothes but also in “class drag” and “ethnic drag”, that is, dressing up as a bourgeoise or a black enslaved woman. Re‑enacted by the performer Werner Hirsch, this gesture raises the question of crossing boundaries laid down by social norms and, to borrow the title of a book by the philosopher Judith Butler, of the visibility of “bodies that matter”.

Rooms 11+13

Words and images

The title of these two rooms comes from René Magritte, who described in a 1929 text titled “Les mots et les images” the poetic use to which he was putting objects and their names in his work. Almost a century later, this turn of phrase by the Surrealist painter invites us to discover the diversity of formal vocabularies artists have developed over time. The works on view here represent a few of them, both suggesting words that translate thoughts and playing with perceptual illusions that alter and transmute forms and meanings. As an introduction, visitors pass through RENÉE GREEN’s Space Poem that is made up of coloured flags sporting lines of a poem written by Laura Riding in the 1930s. In the work of CHÉRIF and SILVIE DEFRAOUI, writing is cut horizontally to become both sign and decoration. Certitudes arise and then crumble in MARKUS RAETZ’s anamorphoses, a distortion also found in the works of GIUSEPPE PENONE, who analyses the mysteries of vision and its representation.

Room 12

Monuments

In 1982, Maya Lin, then an undergraduate architecture student at Yale, won a competition for the design of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, black marble walls like notches in the earth, an explicit counterpoint to the triumphal verticalism and whiteness of Washington statuary. Since then, many artists have transcribed the complexity of memory processes and their representation by making anti‑monuments that emphasize absence, void and loss rather than a unifying narrative. Examples in this case include the Monument Against Fascism by Esther Shalev‑Gerz and Jochen Gerz (Hamburg Harburg, 1986‑93) and Rachel Whiteread’s Holocaust Memorial (Vienna, 2000), but also works made for the museum rather than for a particular public space. Alfredo Jaar’s Real Pictures (1995‑2007) in the MCBA collection, and Gurbet’s Diary by BANU CENNETOĞLU come to mind, and in a more dystopian vein, JULIAN CHARRIÈRE’s Pacific Fiction – Study for a Monument. In their way, all these works are part of an anti‑monument approach to memorialisation while making plain the difficulty of lending concrete form to both the commemoration of violence and the great tragedies of history. In ADRIAN PACI’s film The Column, shown in the adjacent room, it is the very material of monuments, and their displacement in a globalized economy, that take center stage.